- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

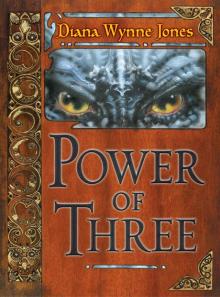

Power of Three

Power of Three Read online

Diana Wynne Jones

POWER OF THREE

Dedication

FOR KIT AND JANNIE

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

About the Author

Other Works

Credits

Copyright

Back Ad

About the Publisher

Chapter

1

THIS IS THE STORY OF THE CHILDREN OF ADARA—of Ayna and Ceri who both had Gifts, and of Gair, who thought he was ordinary. But, as all the things which later happened on the Moor go back to something Adara’s brother Orban did one summer day when Adara herself was only seven years old, this is the first thing to be told.

The Moor was never quite free of mist. Even at bright noon that bright summer day there was a smokiness to the trees and the very corn, so that it could have been a green landscape reflected in one of its own sluggish, peaty dikes. The reason was that the Moor was a sunken plain, almost entirely surrounded by low green hills. Much of it was still marsh, and the Sun drew vapors from it constantly.

Orban was swaggering along a straight green track, away from Otmound, which stood low and turfy behind him, slightly in advance of the ring of hills round the Moor. Beyond it, away to his left, was its companion, the Haunted Mound, which had a huge boulder planted crookedly on top of it, no one knew why. Orban could see it when he turned to warn his sister, loftily over his shoulder, not to go near marsh or standing water. He was annoyed with her for following him, but he did not want to get into trouble for not taking care of her.

It was one of those times when the Giants were at war among themselves. From time to time, from beyond the mists at the edge of the Moor, came the blank thump and rumble of their weapons. Orban took no notice. Giants did not interest him. The track he was on was an old Giants’ road. If he looked down through the turf, he could see the great stones of it, too heavy for men to lift, and he thought he might kill a few Giants some day. But his mind was mostly taken up with Orban, who was twelve years old and going to be Chief. Orban had a fine new sword. He swished it importantly and fingered the thick gold collar round his neck that marked him as the son of a Chief.

“Hurry up, or the Dorig will get you!” he called back to Adara.

Adara, being only seven, was nervous of the Giants and their noise. It was mixed up in her mind with the sound of thunder, when, it always seemed to her, even bigger Giants rolled wooden balls around in the sky. But she did not want Orban to think she was afraid, so she hurried beside him down the green track and pretended not to hear the noise.

Orban had come out to be alone with his new sword and his own glory, but, since Adara had followed him out, he decided to unveil his glory to her a little. “I know ten times as much as you do,” he told her.

“I know you do,” Adara answered humbly.

Orban scowled. One does not want glory accepted as a matter of course. One wants to shock and astonish people with it. “I bet you didn’t know the Haunted Mound is stuffed with the ghosts of dead Dorig,” he said. “The Otmounders killed them all, hundreds of years ago. The only good Dorig is a dead Dorig.”

This was common knowledge. But, since Adara really thought Orban was the cleverest person she knew, she politely said nothing.

“Dorig are just vermin,” Orban continued, displeased by her silence. “Cold-blooded vermin. They can’t sing, or weave, or fight, or work gold. They just lie underwater and wait to pull you under. Did you know half the hills round the Moor used to be full of people, until the Dorig killed them all off?”

“I thought that was the Plague,” Adara said timidly.

“You’re stupid,” said Orban. Adara, seeing it had been a mistake to correct him, said humbly that she knew she was. This did not please Orban either. He sought about for some method of startling Adara into a true sense of his superiority.

The prospect was not promising. The track led among tufts of rushes, straight into misty distance. There was a hedge and a dike half a field away. A band of mist lay over a dip in the old road and a spindly blackbird was watching them from it. The blackbird would have to do. “You see that blackbird?” said Orban.

A blunt volley of noise from the Giants made Adara jump. She looked round and discovered that Otmound was already misty with distance. “Let’s go home,” she said.

“This is one thing you don’t know. Go home if you want,” said Orban. “But if that blackbird is really a Dorig, I can make it shift to its proper shape. I know the words. Shall I say them?”

“No. Let’s go home,” Adara said, shivering.

“Baby!” said Orban. “You watch.” And he marched toward the bird, saying the words and swishing his sword in time to them.

Nothing happened, because Orban got the words wrong. Nothing whatsoever would have happened, had not Adara, who hated Orban to look a fool, obligingly said the words right for him.

A wave of cold air swept out of the hollow, making both children shiver. They were too horrified to move. The blackbird, after a frantic flutter of protest, dissolved into mist thicker and grayer than the haze around it. The mist swirled, and solidified into a shape much larger. It was the pale, scaly figure of a Dorig, right enough. It was crouched on one knee in the dip, staring toward them in horror, and holding in both hands a twisted green-gold collar not unlike Orban’s or Adara’s.

“Now look what you’ve done!” Orban snarled at Adara. But, as he said it, he realized that the Dorig was not really very large. He had been told that Dorig usually stood head and shoulders above a grown man, but this one was probably only as high as his chin. It had a weak and spindly look, too. It did not seem to have a weapon and, better still, Orban knew that those words, once spoken, would prevent the creature shifting shape until Sundown. There was no chance of it turning into an adder or a wolf.

Feeling very much better, Orban marched toward the dip, swinging his sword menacingly. The Dorig stood up, trembling, and backed away a few steps. It was rather smaller than Orban had thought. Orban began to feel brave. He scanned the thing contemptuously, and the collar flashing between its pale fingers caught his attention. It was a very fine one. Though it was the same horseshoe shape as Orban’s and made of the same green gold, it was twice the width and woven into delicate filigree patterns. Orban glimpsed words, animals and flowers in the pattern. And the knobs at either end, which in Orban’s collar were just plain bosses, seemed to be in the shape of owls’ heads on this one. Now Orban, only the day before, had been severely slapped for fooling about with a collar rather less fine. He knew the art of making this kind had been lost long ago. No wonder the Dorig was so frightened. He had caught it red-handed with a valuable antique.

“What are you doing with that collar?” he demanded.

The Dorig looked tremulously up at Orban’s face. Orban found its strange yellow eyes disgusting. “Only sunning it,” it said apologetically. “You have to sun gold, or it turns back to earth again.”

“Nonsense,” said Orban. “I’ve never sunned mine in my life.”

“You live more in the air than we do,” the Dorig pointed out.

Orban shuddered, thinking of the way the Dorig skulked out their lives under stinking marsh water. And they were cold-blooded, too, so of course they would have to sun any gold they stole. Ugh! “Where did you get tha

t collar?” he said sternly.

The Dorig seemed surprised that he should ask. “From my father, of course! Didn’t your father give you yours?”

“Yes,” said Orban. “But my father’s Chief Og of Otmound.”

“I expect he’s a very great man,” the Dorig said politely.

Orban was almost too angry to speak. It was clear that this miserable, tremulous Dorig had never even heard of Og of Otmound. “My father,” he said, “is the senior Chief on the Moor. And your father’s a thief. He stole that collar from somewhere.”

“He didn’t—he had it made!” the Dorig said indignantly. “And he’s not a thief! He’s the King.”

Orban stared. The Giants interrupted with another distant thump and a rumble, but Orban’s mind took that in no more than it would take in what the Dorig had just said. If it was true, it meant that this wretched, skinny, scaly creature was more important than he was. And he knew that must be nonsense. “All Dorig are liars,” he explained to Adara.

“I’m not!” the Dorig protested.

Adara was in dread that Orban was going to make a fool of himself, as he so often did. “I’m sure he’s telling the truth, Orban,” she said. “Let’s go home now.”

“He’s lying,” Orban insisted. “Dorig can’t work gold, so it must all be lies.”

“No, you’re wrong. We have some very good goldsmiths,” said the Dorig. Seeing Adara was ready to believe this, it turned eagerly to her. “I watched them make this collar. They wove words in for Power, Riches and Truth. Is yours the same?”

Adara, much impressed, fingered her own narrower, plainer collar. “Mine only has Safety. So does Orban’s.”

Orban could not bear Adara to be impressed by anyone but himself. He refused to believe a word of it. “Don’ t listen,” he said. “It’s just trying to make you believe it hasn’t stolen that collar.” Adara looked from Orban to the Dorig, troubled and undecided. Orban saw he had not impressed her. Very well. She must be made to see who was right. He held out his hand imperiously to the Dorig. “Come on. Hand it over.”

The Dorig did not understand straightaway. Then its yellow eyes widened and it backed away a step, clutching the collar to its thin chest. “But it’s mine! I told you!”

“Orban, leave him be,” Adara said uncomfortably.

By this time, Orban was beginning to see he might be making a fool of himself. It made him furiously angry, and all the more determined to impress Adara in spite of it. “Give me that collar,” he said to the Dorig. “Or I’ll kill you.” To prove that he could, he swung his new sword so that the air whistled. The Dorig flinched.

“Run away,” Adara advised it urgently.

Finding Adara now definitely on the side of the Dorig was the last straw to Orban. “Do, and I’ll catch you in two steps!” he told it. “Then I’ll kill you and take the collar anyway. So hand it over.”

The Dorig knew its shorter legs were no match for Orban’s. It stood where it was, clutching the collar and shaking. “I haven’t even got a knife,” it said. “And you stopped me shifting shape till this evening.”

“That was my fault. I’m sorry,” said Adara.

“Shut up!” Orban snarled at her. He made a swift left-handed snatch at the collar. “Give me that!”

The Dorig dodged. “I can’t!” it said desperately. “Tell him I can’t,” it said to Adara.

“Orban, you know he can’t,” said Adara. “If it was yours, it could only be taken off your dead body.”

This only made it clear to Orban that he would have to kill the creature. He had gone too far to turn back with dignity, and the knowledge maddened him further. Anyway, what business had the Dorig to imitate the customs of men? “I told you to shut up,” he said to Adara. “Besides, it’s only a stolen collar, and that’s not the same. Give it!” He advanced on the Dorig.

It backed away from him, looking quite desperate. “Be careful! I’ll put a curse on the collar if you try. It won’t do you any good if you do get it.”

Orban’s reply was to snatch at the collar again. The Dorig side-stepped, though only just in time. But it managed, in spite of its shaking fingers, to get the collar round its neck, making it much more difficult for Orban to grab. Then it began to curse. Adara marveled, and even Orban was daunted, at the power and fluency of that curse. They had no idea Dorig knew words that way. In a shrill hasty voice, the creature laid it on the collar that the words woven in it should in future work against the owner, that Power should bring pain, Riches loss, Truth disaster, and ill luck of all kinds follow the feet and cloud the mind of the possessor. Then it ran its pale fingers along the intricate twists and pattern of the design, bringing each part it touched to bear on the curse: fish for loss by water, animals for loss by land, flowers for death of hope, knots for death of friendship, fruit for failure and barrenness, and each, as they were joined in the workmanship, to be joined in the life of the owner. At last, touching the owl’s head at either end, it laid on them to be guardians and cause the collar’s owner to cling to it and keep it as if it were the most precious thing he knew. When this was said, the Dorig paused. It was panting and palely flushed. “Well? Do you still want it?”

Adara was appalled to hear so much beauty spoiled and such careful workmanship turned against itself. “No!” she said. “And do get them to make you another one when you get home.”

But Orban listened, feeling rather cunning. He noticed that not once had the Dorig invoked any higher Power than that of the collar itself. Without the Sun, the Moon or the Earth, even such a curse as this could only bring mild bad luck. The creature must take him for a fool. The Giants began thumping away again beyond the horizon, as if they were applauding Orban’s acuteness. Determined not to be outwitted, Orban flung himself on the Dorig and got his hand hooked round the collar before it could move. “Now give it!”

“No!” The Dorig kept both hands on the collar and pulled away. Orban swung his new sword and brought it down on the creature’s head. It bowed and staggered. Adara flung herself on Orban and tried to pull him away. Orban pushed her over with an easy shove of his right elbow and raised his sword again. Beyond the horizon, the Giants thundered like rocks raining from heaven.

“All right!” cried the Dorig. “I call on the Old Power, the Middle and the New to hold this curse to my collar. May it never loose until the Three are placated.”

Orban was furious at this duplicity. He brought his sword down hard. The Dorig gave a weak cry and crumpled up. Orban wrenched the collar from its neck and stood up, shaking with triumph and disgust. The Giants’ noise stopped, leaving a thick silence.

“Orban, how could you!” said Adara, kneeling on the turf of the old road.

Orban looked contemptuously from her to his victim. He was a little surprised to see that the blood coming out of the pale corpse was bright red and steamed a little in the cold air. But he remembered that fish sometimes come netted with blood quite as red, and that things on a muck heap steam as they decay. “Get up,” he said to Adara. “The only good Dorig is a dead Dorig. Come on.”

He set off for home, with Adara pattering miserably behind. Her face was pale and stiff, and her teeth were chattering. “Throw the collar away, Orban,” she implored him. “It’s got a dreadful strong curse on it.”

Orban had, in fact, been uneasily wondering whether to get rid of the collar. But Adara’s timidity at once made him obstinate. “Don’t be a fool,” he said. “He didn’t invoke any proper Powers. If you ask me, he made a complete mess of it.”

“But it was a dying curse,” Adara pointed out.

Orban pretended not to hear. He put the collar into the front of his jacket and firmly buttoned it. Then he made a great to-do over cleaning his sword, whistling, and pretending to himself that he felt much better about the Dorig than he did. He told himself he had just acquired a valuable piece of treasure; that the Dorig had certainly told a pack of lies; and that if it had told the truth, then he had just struck a real blow at

the enemy, and the only good Dorig were dead ones.

“We’d better ask Father about those Powers,” Adara said miserably.

“Oh no we won’t!” said Orban. “Don’t you dare say a word to anyone. If you do, I’ll put the strongest words I know on you. Go on—swear you won’t say a word.”

His ferocity so appalled Adara that she swore by the Sun and the Moon never to tell a living soul. Orban was satisfied. He did not bother to consider why he was so anxious that no one should know about the collar. His mind conveniently sheered off from what Og would say if he knew his son had killed an unarmed and defenseless creature for the sake of a collar which was cursed. No. Once Adara had sworn not to tell, Orban began to feel pleased with the morning’s work.

It was otherwise with Adara. She was wretched. She kept remembering the look of pleasure in the Dorig’s yellow eyes when it saw she was ready to believe it, and their look of despair when it invoked the Powers. She knew it was her fault. If she had not said the words right, Orban would not have killed the Dorig and brought home a curse. She could have gone on thinking the world of Orban instead of knowing he was just a cruel bully.

For Adara, almost the worst part was her disillusionment with Orban. It spread to everyone in Otmound. She looked at them all and listened to them talk, and it seemed to her that they would all have done just the same as Orban. She told herself that when she grew up she would never marry—never—unless she could find someone quite different. But quite the worst part was not being able to tell anyone. Adara longed to confess. She had never felt so guilty in her life. But she had sworn the strongest oath and she dared not say a word. Whenever she thought of the Dorig she wanted to cry, but her guilt and terror stopped her doing even that. First she dared not cry, then she found she could not. Before a month passed she was pale and ill and could not eat.

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci