- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

The Magicians of Caprona Page 2

The Magicians of Caprona Read online

Page 2

When he was near the Corso, Tonino heard a tourist say in English, “Oh look! Punch and Judy!” Very smug at being able to understand, Tonino dived and pushed and tunneled until he was at the front of the crowd and able to watch Punch beat Judy to death at the top of his little painted sentry-box. He clapped and cheered, and when someone puffed and panted into the crowd too, and pushed him aside, Tonino was as indignant as the rest. He had quite forgotten he was miserable. “Don’t shove!” he shouted.

“Have a heart!” protested the man. “I must see Mr. Punch cheat the Hangman.”

“Then be quiet!” roared everyone, Tonino included.

“I only said—” began the man. He was a large damp-faced person, with an odd excitable manner.

“Shut up!” shouted everyone.

The man panted and grinned and watched with his mouth open Punch attack the policeman. He might have been the smallest boy there. Tonino looked irritably sideways at him and decided the man was probably an amiable lunatic. He let out such bellows of laughter at the smallest jokes, and he was so oddly dressed. He was wearing a shiny red silk suit with flashing gold buttons and glittering medals. Instead of the usual tie, he had white cloth folded at his neck, held in place by a brooch which winked like a teardrop. There were glistening buckles on his shoes, and golden rosettes at his knees. What with his sweaty face and his white shiny teeth showing as he laughed, the man glistened all over.

Mr. Punch noticed him too. “Oh what a clever fellow!” he crowed, bouncing about on his little wooden shelf. “I see gold buttons. Can it be the Pope?”

“Oh no it isn’t!” bellowed Mr. Glister, highly delighted.

“Can it be the Duke?” cawed Mr. Punch.

“Oh no it isn’t!” roared Mr. Glister, and everyone else.

“Oh yes it is,” crowed Mr. Punch.

While everyone was howling “Oh no it isn’t!” two worried-looking men pushed their way through the people to Mr. Glister.

“Your Grace,” said one, “the Bishop reached the Cathedral half an hour ago.”

“Oh bother!” said Mr. Glister. “Why are you lot always bullying me? Can’t I just—until this ends? I love Punch and Judy.”

The two men looked at him reproachfully.

“Oh—very well,” said Mr. Glister. “You two pay the showman. Give everyone here something.” He turned and went bounding away into the Corso, puffing and panting.

For a moment, Tonino wondered if Mr. Glister was actually the Duke of Caprona. But the two men made no attempt to pay the showman, or anyone else. They simply went trotting demurely after Mr. Glister, as if they were afraid of losing him. From this, Tonino gathered that Mr. Glister was indeed a lunatic—a rich one—and they were humoring him.

“Mean things!” crowed Mr. Punch, and set about tricking the Hangman into being hanged instead of him. Tonino watched until Mr. Punch bowed and retired in triumph into the little painted villa at the back of his stage. Then he turned away, remembering his unhappiness.

He did not feel like going back to the Casa Montana. He did not feel like doing anything particularly. He wandered on, the way he had been going, until he found himself in the Piazza Nuova, up on the hill at the western end of the city. Here he sat gloomily on the parapet, gazing across the River Voltava at the rich villas and the Ducal Palace, and at the long arches of the New Bridge, and wondering if he was going to spend the rest of his life in a fog of stupidity.

The Piazza Nuova had been made at the same time as the New Bridge, about seventy years ago, to give everyone the grand view of Caprona Tonino was looking at now. It was breathtaking. But the trouble was, everything Tonino looked at had something to do with the Casa Montana.

Take the Ducal Palace, whose golden-stone towers cut clear lines into the clean blue of the sky opposite. Each golden tower swept outwards at the top, so that the soldiers on the battlements, beneath the snapping red and gold flags, could not be reached by anyone climbing up from below. Tonino could see the shields built into the battlements, two a side, one cherry, one leaf-green, showing that the Montanas and the Petrocchis had added a spell to defend each tower. And the great white marble front below was inlaid with other marbles, all colors of the rainbow. And among those colors were cherry-red and leaf-green.

The long golden villas on the hillside below the Palace each had a leaf-green or cherry-red disc on their walls. Some were half hidden by the dark spires of the elegant little trees planted in front of them, but Tonino knew they were there. And the stone and metal arches of the New Bridge, sweeping away from him towards the villas and the Palace, each bore an enamel plaque, green and red alternately. The New Bridge had been sustained by the strongest spells the Casa Montana and the Casa Petrocchi could produce. At the moment, when the river was just a shingly trickle, they did not seem necessary. But in winter, when the rain fell in the Apennines, the Voltava became a furious torrent. The arches of the New Bridge barely cleared it. The Old Bridge—which Tonino could see by craning out and sideways—was often under water, and the funny little houses along it could not be used. Only Montana and Petrocchi spells deep in its foundations stopped the Old Bridge being swept away.

Tonino had heard Old Niccolo say that the New Bridge spells had taken the entire efforts of the entire Montana family. Old Niccolo had helped make them when he was the same age as Tonino. Tonino could not have done. Miserable, he looked down at the golden walls and red pan-tiles of Caprona below. He was quite certain that every single one hid at least a leaf-green scrip. And the most Tonino had ever done was help stamp the winged horse on the outside. He was fairly sure that was all he ever would do.

He had a feeling somebody was calling him. Tonino looked round at the Piazza Nuova. No body. Despite the view, the Piazza was too far for the tourists to come. All Tonino could see were the mighty iron griffins which reared up at intervals all around the parapet, reaching iron paws to the sky. More griffins tangled into a fighting heap in the center of the square to make a fountain. And even here, Tonino could not get away from his family. A little metal plate was set into the stone beneath the huge iron claws of the nearest griffin. It was leaf-green. Tonino found he had burst into tears.

Among his tears, he thought for a moment that one of the more distant griffins had left its stone perch and come trotting round the parapet towards him. It had left its wings behind, or else had them tightly folded.

He was told, a little smugly, that cats do not need wings. Benvenuto sat down on the parapet beside him, staring accusingly.

Tonino had always been thoroughly in awe of Benvenuto. He stretched out a hand to him timidly. “Hallo, Benvenuto.”

Benvenuto ignored the hand. It was covered with water from Tonino’s eyes, he said, and it made a cat wonder why Tonino was being so silly.

“There are our spells everywhere,” Tonino explained. “And I’ll never be able—Do you think it’s because I’m half English?”

Benvenuto was not sure quite what difference that made. All it meant, as far as he could see, was that Paolo had blue eyes like a Siamese and Rosa had white fur—

“Fair hair,” said Tonino.

—and Tonino himself had tabby hair, like the pale stripes in a tabby, Benvenuto continued, un perturbed. And those were all cats, weren’t they?

“But I’m so stupid—” Tonino began.

Benvenuto interrupted that he had heard Tonino chattering with those kittens yesterday, and he had thought Tonino was a good deal cleverer than they were. And before Tonino went and objected that those were only kittens, wasn’t Tonino only a kitten himself?

At this, Tonino laughed and dried his hand on his trousers. When he held the hand out to Benvenuto again, Benvenuto rose up, very high on all four paws, and advanced to it, purring. Tonino ventured to stroke him. Benvenuto walked around and around, arched and purring, like the smallest and friendliest kitten in the Casa. Tonino found himself grinning with pride and pleasure. He could tell from the waving of Benvenuto’s brush of a tail, in majestic, angr

y twitches, that Benvenuto did not altogether like being stroked—which made it all the more of an honor.

That was better, Benvenuto said. He minced up to Tonino’s bare legs and installed himself across them, like a brown muscular mat. Tonino went on stroking him. Prickles came out of one end of the mat and treadled painfully at Tonino’s thighs. Benvenuto continued to purr. Would Tonino look at it this way, he wondered, that they were both, boy and cat, a part of the most famous Casa in Caprona, which in turn was part of the most special of all the Italian States?

“I know that,” said Tonino. “It’s because I think it’s wonderful too that I—Are we really so special?”

Of course, purred Benvenuto. And if Tonino were to lean out and look across at the Cathedral, he would see why.

Obediently, Tonino leaned and looked. The huge marble bubbles of the Cathedral domes leaped up from among the houses at the end of the Corso. He knew there never was such a building as that. It floated, high and white and gold and green. And on the top of the highest dome the sun flashed on the great golden figure of the Angel, poised there with spread wings, holding in one hand a golden scroll. It seemed to bless all Caprona.

That Angel, Benvenuto informed him, was there as a sign that Caprona would be safe as long as everyone sang the tune of the Angel of Caprona. The Angel had brought that song in a scroll straight from Heaven to the First Duke of Caprona, and its power had banished the White Devil and made Caprona great. The White Devil had been prowling around Caprona ever since, trying to get back into the city, but as long as the Angel’s song was sung, it would never succeed.

“I know that,” said Tonino. “We sing the Angel every day at school.” That brought back the main part of his misery. “They keep making me learn the story—and all sorts of things—and I can’t, because I know them already, so I can’t learn properly.”

Benvenuto stopped purring. He quivered, because Tonino’s fingers had caught in one of the many lumps of matted fur in his coat. Still quivering, he demanded rather sourly why it hadn’t occurred to Tonino to tell them at school that he knew these things.

“Sorry!” Tonino hurriedly moved his fingers. “But,” he explained, “they keep saying you have to do them this way, or you’ll never learn properly.”

Well, it was up to Tonino of course, Benvenuto said, still irritable, but there seemed no point in learning things twice. A cat wouldn’t stand for it. And it was about time they were getting back to the Casa.

Tonino sighed. “I suppose so. They’ll be worried.” He gathered Benvenuto into his arms and stood up.

Benvenuto liked that. He purred. And it had nothing to do with the Montanas being worried. The aunts would be cooking lunch, and Tonino would find it easier than Benvenuto to nick a nice piece of veal.

That made Tonino laugh. As he started down the steps to the New Bridge, he said, “You know, Benvenuto, you’d be a lot more comfortable if you let me get those lumps out of your coat and comb you a bit.”

Benvenuto stated that anyone trying to comb him would get raked with every claw he possessed.

“A brush then?”

Benvenuto said he would consider that.

It was here that Lucia encountered them. She had looked for Tonino all over Caprona by then and she was prepared to be extremely angry. But the sight of Benvenuto’s evil lopsided countenance staring at her out of Tonino’s arms left her with almost nothing to say. “We’ll be late for lunch,” she said.

“No we won’t,” said Tonino. “We’ll be in time for you to stand guard while I steal Benvenuto some veal.”

“Trust Benvenuto to have it all worked out,” said Lucia. “What is this? The start of a profitable relationship?”

You could put it that way, Benvenuto told Tonino. “You could put it that way,” Tonino said to Lucia.

At all events, Lucia was sufficiently impressed to engage Aunt Gina in conversation while Tonino got Benvenuto his veal. And everyone was too pleased to see Tonino safely back to mind too much. Corinna and Rosa minded, however, that afternoon, when Corinna lost her scissors and Rosa her hairbrush. Both of them stormed out onto the gallery. Paolo was there, watching Tonino gently and carefully snip the mats out of Benvenuto’s coat. The hairbrush lay beside Tonino, full of brown fur.

“And you can really understand everything he says?” Paolo was saying.

“I can understand all the cats,” said Tonino. “Don’t move, Benvenuto. This one’s right on your skin.”

It says volumes for Benvenuto’s status—and therefore for Tonino’s—that neither Rosa nor Corinna dared say a word to him. They turned on Paolo instead. “What do you mean, Paolo, standing there letting him mess that brush up? Why couldn’t you make him use the kitchen scissors?”

Paolo did not mind. He was too relieved that he was not going to have to learn to understand cats himself. He would not have known how to begin.

From that time forward, Benvenuto regarded himself as Tonino’s special cat. It made a difference to both of them. Benvenuto, what with constant brushing—for Rosa bought Tonino a special hairbrush for him—and almost as constant supplies filched from under Aunt Gina’s nose, soon began to look younger and sleeker. Tonino forgot he had ever been unhappy. He was now a proud and special person. When Old Niccolo needed Benvenuto, he had to ask Tonino first. Benvenuto flatly refused to do anything for anyone without Tonino’s permission. Paolo was very amused at how angry Old Niccolo got.

“That cat has just taken advantage of me!” he stormed. “I ask him to do me a kindness and what do I get? Ingratitude!”

In the end, Tonino had to tell Benvenuto that he was to consider himself at Old Niccolo’s service while Tonino was at school. Otherwise Benvenuto simply disappeared for the day. But he always, unfailingly, reappeared around half past three, and sat on the waterbutt nearest the gate, waiting for Tonino. And as soon as Tonino came through the gate, Benvenuto would jump into his arms.

This was true even at the times when Benvenuto was not available to anyone. That was mostly at full moon, when the lady cats wauled enticingly from the roofs of Caprona.

Tonino went to school on Monday, having considered Benvenuto’s advice. And, when the time came when they gave him a picture of a cat and said the shapes under it went: Ker-a-ter, Tonino gathered up his courage and whispered, “Yes. It’s a C and an A and a T. I know how to read.”

His teacher, who was new to Caprona, did not know what to make of him, and called the Headmistress. “Oh,” she was told. “It’s another Montana. I should have warned you. They all know how to read. Most of them know Latin too—they use it a lot in their spells—and some of them know English as well. You’ll find they’re about average with sums, though.”

So Tonino was given a proper book while the other children learned their letters. It was too easy for him. He finished it in ten minutes and had to be given another. And that was how he dis covered about books. To Tonino, reading a book soon be came an enchantment above any spell. He could never get enough of it. He ransacked the Casa Montana and the Public Library, and he spent all his pocket money on books. It soon became well known that the best present you could give Tonino was a book—and the best book would be about the unimaginable situation where there were no spells. For Tonino preferred fantasy. In his favorite books, people had wild adventures with no magic to help or hinder them.

Benvenuto thoroughly approved. While Tonino read, he kept still, and a cat could be comfortable sitting on him. Paolo teased Tonino a little about being such a bookworm, but he did not really mind. He knew he could always persuade Tonino to leave his book if he really wanted him. Antonio was worried. He worried about everything. He was afraid Tonino was not getting enough exercise. But everyone else in the Casa said this was nonsense. They were proud of Tonino. He was as studious as Corinna, they said, and, no doubt, both of them would end up at Caprona University, like Great-Uncle Umberto. The Montanas always had someone at the University. It meant they were not selfishly keeping the Theory of Magic to th

e family, and it was also very useful to have access to the spells in the University Library.

Despite these hopes for him, Tonino continued to be slow at learning spells and not particularly quick at school. Paolo was twice as quick at both. But as the years went by, both of them accepted it. It did not worry them. What worried them far more was their gradual discovery that things were not altogether well in the Casa Montana, nor in Caprona either.

Chapter 3

It was Benvenuto who first worried Tonino. Despite all the care Tonino gave him, he became steadily thinner and more ragged again. Now Benvenuto was roughly the same age as Tonino. Tonino knew that was old for a cat, and at first he assumed that Benvenuto was just feeling his years. Then he noticed that Old Niccolo had taken to looking almost as worried as Antonio, and that Uncle Umberto called on him from the University almost every day. Each time he did, Old Niccolo or Aunt Francesca would ask for Benvenuto and Benvenuto would come back tired out. So he asked Benvenuto what was wrong.

Benvenuto’s reply was that they might let a cat have some peace, even if the Duke was a booby. And he was not going to be pestered by Tonino into the bargain.

Tonino consulted Paolo, and found Paolo worried too. Paolo had been noticing his mother. Her fair hair had lately become several shades paler with all the white in it, and she looked nervous all the time. When Paolo asked Elizabeth what was the matter, she said, “Oh nothing, Paolo—only all this makes it so difficult to find a husband for Rosa.”

Rosa was now eighteen. The entire Casa was busy discussing a husband for her, and there did, now Paolo noticed, seem much more fuss and anxiety about the matter than there had been over Cousin Claudia, three years before. Montanas had to be careful who they married. It stood to reason. They had to marry someone who had some talent at least for spells or music; and it had to be someone the rest of the family liked; and, above all, it had to be someone with no kind of connection with the Petrocchis. But Cousin Claudia had found and married Arturo without all the discussion and worry that was going on over Rosa. Paolo could only suppose the reason was “all this,” whatever Elizabeth had meant by that.

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

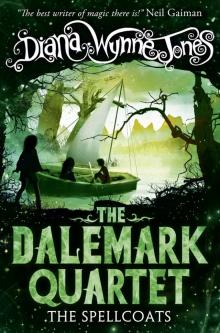

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

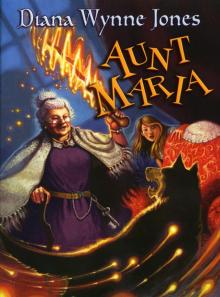

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

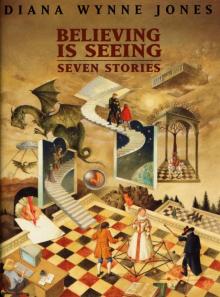

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

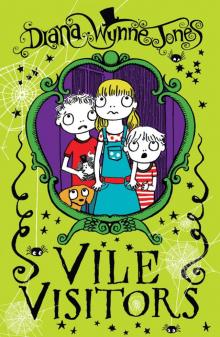

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci