- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

Year of the Griffin Page 25

Year of the Griffin Read online

Page 25

“We forgot heat and neglected to provide gravity,” Felim said, shivering ruefully. “Is there perhaps some means of reversing ourselves?”

“I’d need something to kick off from before I could turn us,” Kit said.

Corkoran moaned again. “We won’t find anything now before the air runs out.”

They all looked anxiously at what they could see of the compressed air at the rim of the sphere. It was almost impossible to tell how thick it was. The blue haze looked different from every angle. Elda supposed it was a comfort to know there was still some there. “Do, please, try not to be so depressing,” Olga said to Corkoran. “Think how lucky it is that we all came, too. You’d hate to be all alone.”

“But you’re using the air up!” said Corkoran. “All of you. The griffins most of all. You’re killing me!”

Nobody tried to point out to Corkoran that he had been wanting to travel like this for years, or that they had been trying to please him—or, anyway, show him it could be done. They were all too anxious. Ruskin did mutter, from the midst of his heat spells, something about ungrateful bunny rabbits, and Blade, still sending Ruskin power, said, “You know, I just don’t understand. This is really only a simple translocation. Normally when you translocate, you get there almost at once.”

“We must be going rather a long way then,” Lukin said.

He had hardly spoken when they were there, wherever it was. With merest soft grinding, the sphere stopped. It was up to its middle into red stony earth, and the sun was blinding across them from a sky that was a curious color, between pink and blue. Despite the sunlight, it was still severely cold. They all scrambled to their feet and stared anxiously over bare desert into a distance that struck them as being rather too near. Their long, peculiar shadows stretched halfway to the horizon. As they stared, the sunlight grew stronger and the sky pinker, and they all somehow began to grasp that it was dawn here. Just as the sun grew strong enough to hide the veiled stars behind the pinkness, two rather small moons hurtled across the sky.

This seemed to be the last straw for Corkoran. He put his hands to his face and screamed.

“A screaming wizard is all we need!” Kit said, and he slapped a stasis spell on Corkoran. Corkoran’s eyes bulged with horror, but at least his screaming stopped.

“Ah, that’s not kind,” said Claudia.

“You’re right,” Kit admitted. “It’s not his fault he’s useless.” He took the stasis off and made Corkoran unconscious instead. Nobody protested.

“Apologies,” Blade said as Corkoran flopped to the rounded floor. He did not fall nearly as heavily as they might have expected. Blade frowned about this as he said to Claudia, “Kit and I have just come from a war, and I’m afraid we both got used to being ruthless. Why were you the only person who wasn’t scared stiff on the way here?”

Claudia flushed a dark olive and looked down so that her hair coiled in and hid her face. “It’s my jinx,” she said. “It’s mostly a travel jinx. I always have trouble traveling, but I always get where I was going in the end. So I knew we’d arrive somewhere, you see.”

“You might,” said Kit, “have warned us you had a jinx. Was that what made that spell on the cloakrack so tangled?”

“I think so,” Claudia admitted, with her head still down.

“And collected us all together and dumped us in this hole?” Kit persisted.

“Er,” said Lukin, “some of that was probably mine. I always make a pit of some kind when I do any magic.”

“Don’t criticize this hole,” Ruskin said, huskily even for him. “I reckon we freeze or burn here without it. Wherever here is,” he added. “We ought all to keep well down inside it.”

As everyone hurriedly sat or crouched down, Felim said, “This is a lesson to me not to rely on my honor to rule my actions. I am well served. I thought I was right and Corkoran was wrong, and look where we are now!”

Kit, who knew how it felt to have your pride crushed, said, “You were right. We got here. It just needed a bit more thinking through. Nobody reckoned on two jinxes either. If we had, we’d be on the moon at this moment. Where do you think we are?”

Felim seemed slightly comforted. “All the same,” he said, “I shall be more cautious in the future if we ever get away. As to where this is, I have a feeling that Corkoran was screaming because he knew. Should we rouse him and ask him?”

Blade looked at Corkoran curled up among their legs. “We may have to,” he said, “if we can’t work it out for ourselves. The problem is that I have to know where I am in order to go somewhere else. Kit can push me, but I take us. Kit, when we do go, reckon for everything being lighter here, won’t you?”

Ruskin slapped his knee so hard that his hand bounced. “Now that is the attitude I like! Not if, but when we go. That’s positive wizarding, that is!”

“We were taught that way,” said Blade. “But I don’t want to sit and watch the world go past the way the moon did. Before we do anything else, we’re going to unravel these jinxes.”

“Air?” asked Kit. “Doesn’t that come first? Is there any air here at all?”

Olga edged forward. “Maybe I can ask,” she said. When everyone turned to her in confusion, she pushed her hair back and said, “Well, you see, there are some very queer sorts of elementals looking in at us from the sides of this pit. They’re awfully interested, and they might help.”

Naturally everyone craned to look at the sides of the pit. Not all of them could see the beings Olga meant. Of those who could see them, Ruskin and Lukin had the least trouble. Kit and Elda kept turning their heads this way and that because, from the very tails of their eyes, they thought they could see faces there, like clods of earth with round pebblelike eyes, but when either of them turned to look full on, there was just reddish earth. Claudia thought she glimpsed one face, but that was all. Blade and Felim saw nothing but dry, stony earth, anyway.

Olga shut her eyes and tried to listen to the dry, stony voices. It was like hearing a foreign language that was mostly clicks and faint pattering, a language Olga felt she had once learned and then forgotten. As she listened, the words seemed to come back to her slowly. “They want to know,” she said after a while, “if we really are from the blue world. The air elementals in the bubble with us say we are, and they can’t believe it. I’ve told them we are. And they say this is the red world.”

Everyone started speaking at once. “Ye gods! We’re on the Red Planet!” Blade exclaimed. “The dragons call it Mars,” said Kit. “Oh, damn my jinx!” wailed Claudia. “We came a long way out of our way then!” Felim remarked. “How do we get back?” demanded Elda. “How much air do our air elementals say we’ve got?” Ruskin asked urgently, and Lukin said, “Can’t you use our elementals to translate for you?”

“I don’t want to hurt their feelings,” Olga answered Lukin. “I’m getting what they say more clearly now. Now they’re saying that we seem awfully big and soft. They’re wondering about the way the light from the sun is going right through us.”

They all noticed at once that it was getting very hot in the bubble now that the sun was climbing. Kit said, “Oh, lawks!” and a thing like a huge umbrella shot out of the bubble top and hovered over it. Unfortunately it took some of their precious air with it as it opened. They all heard the whoosh and exchanged anxious looks in the sudden shadow. The pit now felt icy. Warm drops of water formed under the umbrella and went running down the bubble inside and out. This made the rim of compressed air much easier to see. It was much less than half as thick as it had been.

“All huddle together,” said Blade. “I daren’t do another warmth-working. I think magic may use more air than anything else does.”

They all moved closer together, except Olga, who remained leaning against the wet side of the bubble. She said dreamily, “Now they’re saying they haven’t seen melted water for thousands of years. They’re fascinated. I asked about air here. They say the air elementals are all frozen, too.”

It was getting fairly stuffy in the damp shade. “Ask them to send us some air,” Ruskin said, “before we smother. I’ve been in mines with more air than this!”

Olga listened again. “There’s an argument about that,” she said, to everyone’s dismay. “The air ones want to come. They want to see our world. But the earth ones say it’s not fair. They want to see the blue world, too.”

“Tell one of them to get in here with us,” Blade suggested tensely. “I can make a link between it and the rest of them, so that they see what it sees.”

There was a long, long pause. Then Olga pushed her hair back and held out both hands. What looked like a simple clod of the reddish earth detached itself from the surface of the pit and hopped like a toad, straight through the surface of the bubble and into Olga’s hands. She held it up to her face, smiling, as if she were holding a kitten. “I can make the link,” she told Blade. “No need to worry. The air ones are coming now.”

There was a pattering and a pinging from all over the outside of the bubble and a frothy rushing-feeling from underneath where they all sat. Little bright bits like snowflakes came swirling in under the umbrella, and from the sides and bottom of the pit, and attached themselves to the outer surface of the sphere like iron filings clinging to a magnet. In seconds there was a thick layer of them all around, whitish and shining. They all felt they were inside a snowdrift. The light was dim and pinkish blue. But it was noticeably easier to breathe.

“Thank you,” Ruskin said devoutly. “Tell them thank you, Olga.” His face suddenly streamed with sweat, and sweat dripped in the plaits of his beard. They all looked at him and looked away quickly, realizing that being without air was a dwarf’s most hideous nightmare. Ruskin had been living in that nightmare until this moment.

As frozen air elementals continued to patter onto the outside of the sphere, and the earth clod sat between Olga’s hands exuding smug excitement, Blade turned to Claudia. “What exactly does your jinx do?”

Claudia spread her thin olive palms out expressively. “This! It messes everything up. Twists it. Everything, particularly magic. It’s at its very worst when I travel, but it’s terribly ingenious, too, so that I can’t guard against it. Something different happens every time. I’ve had snowstorms in summer and landslides and flash floods and things struck by lightning. People go to the wrong place to meet me, or we miss the supply cart, or the road subsides and we have to go around it. Or the horses go lame or trees fall across the track or, or … I’ll tell you, coming to the University, I lost our map—I think ants ate it!—and we went miles out of our way to the east, until the road just ended in a cliff. So we turned back. The legionaries said they’d try to get me back to Condita—they’d gone all grim and sarcastic, the way people do after a taste of my jinx—but instead we blundered into a wet forest full of alligators and went north avoiding that. And then it rained and rained, and when the rain stopped, we saw the University city on the horizon. So we went there. Luckily Titus had made us set off in plenty of time. He always does these days. And I did get there in the end, because that’s the way it works.”

“Let’s get this straight,” said Blade. “You weren’t using magic to travel with, were you?”

“Of course not,” said Claudia. “The legionaries would have hated it.”

“Perhaps she should have been,” Kit suggested. “It sounds like a powerful translocation talent that’s got bent out of shape somehow.”

“It does,” Blade agreed thoughtfully. “And when she does put magic consciously with traveling, it brings us to another planet. It’s strong all right.”

“But other magic things go wrong, too,” Claudia pointed out.

“Well, they would,” Blade explained. “Everyone has one or maybe two major abilities. Olga’s is talking to things I can’t even see, for instance. And if the major talent gets deformed somehow, all the rest goes wrong, too.”

Olga, with her face pink in the strange shadowy light, looked at Lukin and murmured, “That explains my monsters.”

Blade sat with his knees up, chin in hands, elbows on bony knees, staring thoughtfully at Claudia. She looked miserably away from him. “Sorry,” Blade said. “You’ve realized, have you? It’s your feelings that are deforming your magic.”

“I refuse,” Claudia said, with her head bent. “I refuse utterly to believe that Wermacht was right!”

“I don’t know what Wermacht said,” said Blade. “But it’s an awful pity. You feel to me as if you ought to be as strong as Querida really. Let me think—I’ve been to Condita lots of times, but I only ever met you there once. You must have been away a lot.”

Claudia nodded. “I expect I was away in the Marshes with my mother. She insisted I spent half my time with her.”

“And which did you like best, the Empire or the Marshes?” Blade asked her.

Claudia began to speak. “I—” she said, and then put both hands to her face and stopped. “I always tried to kid myself,” she began again, “that I liked both of them equally. But now that it seems important to admit it, I know I hated both of them equally. I mean, I’m fond of Mother, or I would be if she ever stopped grumbling, and I adore Titus, but when I’m in the Marshes, everyone and everything make it plain to me that I’m Empire born and don’t fit, and when I’m in the Empire, it’s worse, because they think of me as dirty Marshwoman—scum, marsh slime, all that. Are you trying to make me admit that my jinx is because I’m a half-breed?’ There were tears in her eyes, big and shiny and greenish in the peculiar snowdrift light.

Blade shook his head emphatically. “No, no, no. Mixes usually make stronger magic. Look at Kit and Elda: They’re lion, eagle, human, and cat. No, what I’m getting at is that you’ve spent most of your life shuttling between two places you hated, and you probably have a fiercely strong translocation talent, anyway, so of course it went wrong. It was your way of kicking and screaming as they dragged you back and forth.”

The tears in Claudia’s eyes spilled out and rolled down her narrow cheeks. “Of course that’s what it is! I should have seen. But—what do I do about it?”

“Forget your childhood. It’s over,” said Blade. “You can be a wizard now and go anywhere and do anything you want.”

Claudia stared at him, still with her hands to her tear-marked cheeks. A slow smile of relief began to spread on what could be seen of her face. “Oh!” she said, and took a deep breath of the chilly, heady new air. As she did so, Blade gave Kit a slight nod. Kit’s mighty talons reached out and tweaked.

“Got it,” he said, whisking something invisible away through the snowy side of the sphere. “One jinx gone. One to go.”

“I know all about mine,” Lukin said defensively. “Mine happens because I don’t want to be a king. When I think about ruling, I just want to dig myself a deep pit and stay in it. So it’s quite obvious and natural that whenever I do magic, I make a hole in something. There’s nothing anyone can do about that.”

Felim had listened appreciatively as Blade coaxed Claudia’s jinx out of her. Now he leaned forward and joined in. “Why do you not want to be a king?” he asked. “This continues to puzzle me, for I know that in my case I would far rather be a wizard, but I know that you have another kind of mind that spreads wider than a wish to sit and study spells.”

Lukin blinked a bit. He thought. “You have to be so strict if you’re a king,” he said at last, rather fretfully. “Everything has to be just so, because you have to set an example, and there’s no money—and by the time I’d get to be king, there’ll be even less money—and we can’t ever seem to heat the castle, and nothing ever really goes right because the tours laid the kingdom to waste, and—”

“Hang on,” said Blade. “You’re talking about the way things are, in Luteria, and the way your father behaves, not about being a king. Just because your father’s the gloomiest man I know, it doesn’t follow that you have to be.”

“Or mismanage money the way he does,” added Kit.

Ruskin wh

o, as a dwarf and a future citizen of Luteria, had been attending to this keenly, looked deeply shocked. “Mismanages money?”

Lukin said angrily, “He doesn’t mismanage money! There just isn’t any!”

“Our dad’s always saying he does,” Elda chipped in. “Derk says King Luther seems to think it’s beneath him even to think about making money.”

Lukin became angrier still. “My father can’t breed winged horses or make a mint of money out of clever pigeons, the way yours can!”

“Yes,” said Kit. “But you could.”

Lukin glared at him. His teeth were so tightly clenched that the muscles bulging in his cheeks, in the strange light, made his face look like a wide, sinister skull. Kit glared calmly back. “I wish you weren’t bigger than me!” Lukin said without taking his teeth apart.

“Hold your hammer,” said Ruskin. “I’m with Felim here. I don’t understand. You met the forgemasters. They love their power. They’d kill to keep it. Why don’t you?”

Lukin shrugged and unclenched his teeth a little. “It doesn’t bother me. I don’t have any power.”

“So you went to train as a wizard in order to get some,” Blade said. “Fair enough. Then what don’t you like? The responsibility? I’d have thought you’d quite like being the one in charge.”

“I would,” Lukin admitted. “Only I’m not, am I? To listen to my father, you’d think I was still ten years old. It’s not his fault. He missed a whole hunk of our lives when Mother took us away into the country because of the tours, and he still hasn’t caught up. There’s a gap—” He stopped suddenly.

Olga looked up from the happy clod cradled in her fingers and surveyed Lukin through the hanging sheet of her hair. “I knew you’d see it in the end,” she said. “Remember magic doesn’t think in a reasonable way, the way people do. Yours just peppers everything you do with that gap your father doesn’t notice, trying to show him you’re grown-up now. Doesn’t it? Didn’t you tell me you first started making pits when the tours stopped and you came home?”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

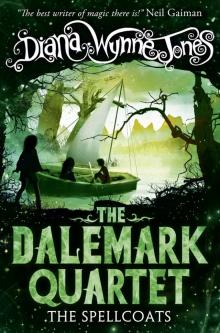

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

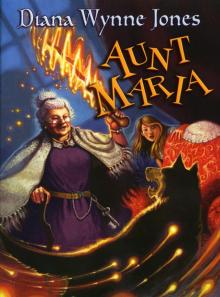

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

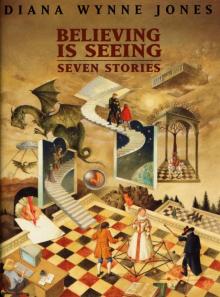

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

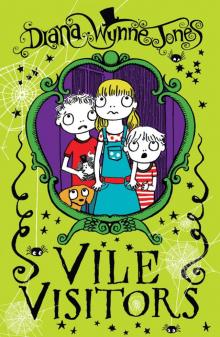

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci