- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

The Merlin Conspiracy Page 26

The Merlin Conspiracy Read online

Page 26

Because it was so hot, we went back by water-bus. Toby showed me the ground where the hurley team he followed played. They didn’t have football. Hurley is much more dangerous. Toby followed the Vauxhall Vampires, and two of them broke their necks at it last week. Vox Vamps, you say, or just Vamps, like we say Wolves or Hammers.

I liked Toby a lot. It was a new experience for me. I wasn’t used to liking someone so much younger than me.

We got home to find that Maxwell Hyde had just come in, too.

“That was quick!” I said.

He gave his little soldierly grin. “Ah, I’m an old hand, Nick. I went straight to the head of things and made inquiries at the Academy of Mages. Told them I was the Magid looking into the recent infiltration in Marseilles.” That made me laugh. He looked solemn. “It’s absolutely true. I am and I was. And they told me, without any beating about the bush. Those poor fellows did get into some trouble, I’m sorry to say. They were removed from any Royal Security that night. But nobody thought it was their fault. They were just blamed for not noticing you weren’t the right novice. Inefficiency and so on. And because fully trained mages are much in demand, all four of them have found new jobs already. Charles Pick and Pierre Lefevre now work in France, and Arnold Hesse and David Croft are in Canada for Inland Security there.”

You can’t imagine how relieved I was to hear that.

“Where’s Canada?” Toby asked.

“A part of North America,” said his grandfather. “In some worlds, Europeans settled quite a lot in—”

He never finished that explanation. Dora suddenly dashed in, white as a sheet. She slammed the living room door and stood with her back to it, shaking. “Don’t go into the garden!” she gasped. “I went for a lettuce.”

“What did it do? Bite you?” Maxwell Hyde asked.

She shuddered. “No. I never got that far. There’s a white devil on the lawn. With horns!”

“What?” said Maxwell Hyde. “Are you sure?”

Dora shuddered some more. “Oh, yes. It was quite real. I know I lose touch quite often, but I always know when something I see is real. It was eating the dahlias.”

At this Maxwell Hyde thundered, “WHAT?” and set off for the garden like an Olympic sprinter. Dora got whirled aside, and Toby and I pelted past her, full of curiosity.

In the baking garden the white devil looked up from a flower bed with a leaf fetchingly dangling beside its beard, saw Maxwell Hyde, and came prancing toward him, obviously delighted to see him.

Maxwell Hyde stopped in his tracks. “Nick,” he said, “do I, or do I not, know this goat?”

“Yes,” I said. “It’s Romanov’s. It must have followed you somehow.” I did wish it was Mini instead. I suddenly, hugely wished Mini was there. It was like being homesick.

“But why?” said Maxwell Hyde. The goat was frisking around him, making playful scything motions with its horns. I could see the rope we had tied round its neck and the frayed end where it had bitten it through.

“It’s fond of you,” I said. “You conquered its heart by taking hold of its horn and its rump and rushing it about.”

Maxwell Hyde managed to grab the bitten end of the rope. “Pooh!” he said. “I’d forgotten the way goats smell.” He tried to snatch the leaf hanging out of the goat’s mouth, but the goat deftly swallowed it as his fingers reached it. “I hope that dahlia poisons you; it was my Red Royal Button,” he said. “What was its name? I forget.”

“Helga,” I said.

The goat tried to bite a lump out of his trousers. He took it by the horns and held it off. “Helga, the goat from hell,” he said. “I think it’s starving. Toby, go and tell your mother to ring up the nearest animal feed merchant and order a ton of goat food. Nick, get to the garden shed. We need a stake, a mallet, and the strongest clothesline you can find.”

“Wouldn’t a chain be better?” I suggested.

“Yes, but I’m going to use magic as a temporary measure,” he panted. The goat was getting strenuous. “Hurry up!”

It turned out to be a violently busy evening.

Toby and I hammered the stake into the lawn—not very easily. Toby hit me on the toe with the mallet, so I took it off him, but the earth was so hard I could hardly get the stake to go in. But that may have been because I kept missing it with the mallet. When I got it sort of in, Maxwell Hyde wrestled the goat over, and we tied her to the stake, where she couldn’t eat dahlias.

This happened three times, because every time Maxwell Hyde walked away, the goat lunged after him and the stake came out of the lawn. Toby got her to stay put in the end by finding her a lump of stale prettybread. After that Maxwell Hyde hammered the stake in himself.

We had just finished when a motorized cart drew up at the front door, piled high with nourishment for goats. Toby and I staggered backward and forward through the house with bales of hay and sacks of nugget things. One of the sacks burst. We dragged it all out on to the lawn, where Maxwell Hyde surrounded the goat knee deep in food, and she weighed into it just as if she hadn’t already eaten half a bed of flowers and most of a prettybread.

“There. What did I say?” he said. “She was starving.”

It seemed to me that this was a permanent condition with that goat, but I didn’t say so.

The shock of meeting the goat seemed to have put Dora in touch with reality much more firmly than usual. She objected—just like an ordinary person—to the hall and the back room being covered with wisps of hay and rolling nugget things. She made Toby and me clear it up. While we were doing this, the phone rang. At least it wasn’t quite a phone. In Blest they call the things far-speakers, and they work mostly the way a phone does, except that they go off like an old-fashioned alarm clock at first. This makes you jump out of your skin. But if you don’t answer them straightaway, they go on to make a horrible, strangled, warbling sound, which is worse.

Dora gave a shriek and went to answer it before it got to warbling.

As soon as she did, she gave another shriek and held the phone thing out as if it was contaminated. “Toby! It’s your father! Come and talk to him.”

Things got difficult then. It turned out that Toby’s dad was insisting on his rights as a parent. He wanted Toby to come and stay with him. Dora refused to let Toby go near him. Maxwell Hyde had to tear himself away from watching Helga guzzle and talk to Toby’s dad, too. While he did, Dora sat on the old sofa at the side of the hall and kept saying, “If you let Toby go near that man, I shall go mad, Daddy, I really shall!” In between, she said, “Don’t forget it’s my magic circle again tonight. I don’t want to take my bad feelings there.”

I thought we were never going to get any supper. I went away and had a bath instead.

When I came downstairs again, the hall was full of drifting transparent creatures—the slender, wavy kind that seem to like emotions—and everything seemed to be settled. Maxwell Hyde was going to drive Toby over to his dad for the day on Friday. He said I should come with them so that I could see the country. Dora seemed to think that between us we could save Toby from his father, so that was all right.

I was sent out for some sticky cakes to celebrate, and to my great relief, we had supper. Afterward Dora decked herself out in her black outfit, and the rest of us settled down peacefully.

Toby and his grandfather had a complete ritual in the evenings. Everything happened in order. First, they turned on the media and sat in two special chairs to watch it. The media was like television, except that it looked more like a picture frame on the wall and only ever seemed to show news or hurley games. If you wanted soaps, you read a book. If you wanted music, you went to a concert or put on a cubette. I read a book because the news was always dead boring and I didn’t understand hurley.

The hurley came first. I heard dimly behind what I was reading that the Vox Vamps had lost their third game in a row and were sacking their manager. Sounds familiar, I thought, and read on. It was quite a good book that Maxwell Hyde had recommended.

I was deep in it when I heard, “Today the King himself met with Flemish trade officials in Norfolk, in an effort to solve the currency dispute …” and I looked up vaguely, hoping they were showing their King.

The King was in the picture as I looked. He was kingly and tall, with a neat beard, and there was a young fellow with him who was the eldest Prince. They were walking across some flat grass, where, in spite of the bright sun, you could see it was very windy. Their coats were flapping, and so were the coats of the businessmen walking to meet them. I had a moment, looking at all those gray suits, when I thought I was back home on Earth. But as the wind blew the coats aside, I saw they all had different bright linings—quite unlike businessmen on Earth.

I was going back to my book when the camera—or whatever they use on Blest—went panning round the rows of smartly dressed people in the background. I went on looking because I thought I might spot Roddy there. But they all seemed to be adults. The newscaster said, “Negotiations have been interrupted twice today by a dispute among the Court wizards …”

“Hey, what’s this?” said Maxwell Hyde.

“The dispute was only settled when the King agreed to accompany the wizards to an undisclosed site elsewhere in England,” the media said. Then they went back to a hurley game.

“What site? What is this? What are they up to?” Maxwell Hyde jumped out of his chair and rushed to the far-speaker.

He was gone for about half an hour. He came back looking displeased and rather puzzled, saying, “Well, I don’t know. Daniel seems to be in a meeting about it. They couldn’t contact him, and I had to get on to the Chancellor’s office instead. Some fool of a clerk who didn’t really know anything. She seemed to think that it wasn’t really a dispute, just some idiot suggestion from that stupid cow Sybil. Those are my adjectives, by the way; the young lady gave me official-speak and gave almost nothing away, if she even knew, which I doubt. All she really knew was that the King has nothing to do with it, whatever it is. Storm in a teacup, by the sound of it. Get the board game out, Toby.”

So they went on to the next bit of their routine, which was this game the two of them played every night. It was really passionate. They sat facing each other over a small table with the board and pieces on it, as tense as people could be, and if you couldn’t tell by their faces how tense they were, you could tell by the number of transparent creatures who came crowding around them. Both of them were ready to kill to win.

They’d offered to teach me this game, but I couldn’t understand the rules of it any more than I could understand hurley. I watched them a bit, out of politeness, but all it did for me was make me homesick for my computer games. My computer wouldn’t work in Blest anyway. They use quite a different system. I went back to my book.

I’d read about a chapter, and Maxwell Hyde had moved on from low moaning, because Toby seemed to be winning, to his usual unfair attempt to persuade Toby to be kind to his poor old decrepit grandfather, when Dora came back.

Dora sailed into the main room with her eyes wide and dreamy and a silly smile on her face. But such a blast of terror and pain came in with her that all three of our heads whipped round. She was carrying some kind of creature by its tail.

All I saw of it was a mistiness and a blur because Maxwell Hyde jumped up and slapped the thing out of her hand. The table went over with a crash, and the creature bolted under the big cupboard. “Dora!” he said.

She gave him a bewildered look. “It was only a salamander, Daddy.”

“Whatever it is, it’s a sentient creature!” Maxwell Hyde told her angrily. “You’ve no business carrying it around like that!”

“But we’ve all got one in the circle!” Dora protested. “They’re to enhance our magic.”

“Are they now?” he said, and he took her by one rattling black sleeve and led her to his chair by the table, which Toby had just put upright. “Sit there,” he said, “and write me out the names and addresses of all the people in this magic circle of yours.” A piece of paper appeared in front of Dora. Maxwell Hyde unclipped the pen from his top pocket and pushed it into her hand. “Write,” he said.

“But why?” Dora looked up from under her hat at him. She really did not seem to understand.

He barked at her, “Just do it! Now!” and rattled the paper angrily under her nose.

She went white and began writing. Meanwhile Toby, who had been collecting dropped game pieces, picked up one that had rolled near the cupboard and asked, “Shall I try to tempt the salamander out?”

“No. Leave it,” Maxwell Hyde said curtly. “Poor thing’s mad with terror anyway. Nick, go to the cupboard under the stairs and fetch out any baskets you can find with lids to them.”

“But won’t it set fire to the house?” Toby asked as I was opening the door.

“I’ll surround it in a field of water. Keep writing, Dora. Get on, Nick,” Maxwell Hyde said. “This is urgent.”

THREE

I found a lunch basket, a smelly fishing creel, and a fancy thing with raffia flowers on it. “Will these do?” I asked.

Maxwell Hyde was leaning over Dora, counting names and addresses. “Perfect,” he said, not looking at me or the baskets. “This is only eleven, Dora. And you make twelve. There has to be thirteen of you, hasn’t there? Who’s your head wallah?”

“Oh, I forgot Mrs. Blantyre,” Dora said, and wrote again.

Maxwell Hyde more or less snatched the paper from under the pen. “Come on, boys,” he said. “Follow me. Bring the baskets.” He marched out of the house into the warm, dark blue evening and slammed the front door behind us. “Luckily,” he remarked as he strode down the street with us hurrying after him, “all these silly people live within walking distance. I think we’ll start with Mrs. Blantyre. Evil old biddy.”

I gave Toby the fishing creel to carry. “What are we doing?” I asked Maxwell Hyde.

“Rescuing salamanders, of course,” he said. “Before they set half London on fire. Before anyone gets a chance to torture them. Two things you should both know,” he went on, swinging round the corner in the direction of the Thames. “One, salamanders are not native to this country. Most of them come from Morocco or the Sahara. So it follows that someone has deliberately imported these. Probably in appalling conditions. And two, salamanders, if hurt or frightened enough, give off an extremely strong discharge of magic. If the witch tormenting them is like Dora’s lot—an idiot—then the magic almost instantly becomes a violent burst of fire. Do you see now why we’re in such a hurry?”

We did. We half ran behind him, baskets bumping, down that street and the next, until we came to a nice little house in a quiet mews. Maxwell Hyde hammered with its little brass knocker. The door was opened, after quite a while, by an old lady with loopy hair, who peered at us sweetly over little half-moon glasses.

“Evening, Mrs. Blantyre,” Maxwell Hyde said. “I’ve come for your salamanders, please.”

Mrs. Blantyre blinked, very, very sweetly. “What salamanders, dear?”

“I haven’t got time for this,” Maxwell Hyde said. And he raised Magid power. He looked just the same, but he suddenly became quite awesome. He stood there as strong as a great mountain or a huge natural disaster. I looked on with interest. It was more or less what I used to do when I was small and older kids tried to bully me. “I’ll have your salamanders,” he said. “Now.”

She took one look and trotted away into her house. She came back again a few seconds later holding a tiny cage that exuded dim light and blasts of panic and horror. “Here, dear. I can’t think why—”

Maxwell Hyde took the cage and tipped the three terrified, misty occupants into the fishing creel. “Tell them they’re safe now, Toby. Make it strong. Where did you get these, Mrs. Blantyre?”

“I can’t think why—” Mrs. Blantyre said again.

“Tell me,” Maxwell Hyde said. “You might as well. I’ll find out anyhow.”

Mrs. Blantyre looked sweetly hurt. “If you really insist. They come from a

dear little junkshop out in Ealing, dear. Tonio’s Curios. They only cost sixpence a dozen. I can’t think why—”

“Thank you,” said Maxwell Hyde. “Good evening, madam. So she’ll have bought twenty-four,” he told us as we hurried away, “to go round thirteen. Elevens into twenty means that most of the others are going to have two each. Damn!”

As we hurried on to the next address, Toby began to have trouble. The salamanders were still terrified and still heating up. The creel started to stink of hot fish. I took it off him and raised it up to my face, where I tried to give the poor things a shot of the power that had conquered Mrs. Blantyre. “It’s all right,” I said. “We’ve rescued you. You’re going to be safe now. It’s okay!”

They sort of believed me. It was interesting. They had proper thoughts, like Mini, tiny, desperate thoughts, and they understood me. They simmered down a bit, and Toby took the creel and took over soothing them again.

It was fairly hectic. We rushed from house to house in the dark, and Maxwell Hyde intimidated person after person into giving up terrified, despairing salamanders. We filled the creel and the lunch basket with them and began on the raffia basket, which began smoking and crackling almost at once, until I more or less shouted at it. And twice Maxwell Hyde had a real row on a doorstep, when someone pretended they had only got one salamander and he knew they had two. They shouted after him that they were calling the police.

The twelfth house we went to was on fire. Rolls of orange-tinted smoke were coming from its downstairs windows, and the fire engine was clanging its way down the street to it as we got there. The front door of the place crashed open. An old fellow came staggering out, shouting, “Help!”

Toby and I dived to catch the two salamanders that shot out with him. Toby got his, but I was carrying two of the baskets, and I missed mine. It streaked down the nearest drain and vanished. It’s probably still around in the sewers somewhere.

“I only dipped them in water!” the old fellow said indignantly to Maxwell Hyde. “That’s all I did, dipped them in water!”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

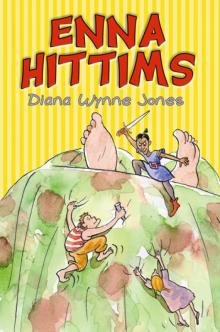

Reflections Enna Hittms

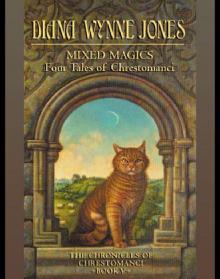

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci