- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

Vile Visitors Page 3

Vile Visitors Read online

Page 3

“Oh, you can’t throw it out!” Mum said. “It’s got such a personality!”

“But it’s worn out,” said Dad. “It wasn’t new when we bought it. We can afford to buy a much nicer one now.”

They argued about it, until Simon began to feel sorry for the old chair and even Marcia felt a little guilty about burning a chair that was old enough to have a personality.

“Couldn’t we just sell it?” she asked.

“Don’t you start!” said Dad. “Even the junk shop wouldn’t want a mucky old thing like—”

At that moment, Auntie Christa came in. Auntie Christa was not really an auntie, but she liked everyone to call her that. As usual, she came rushing in through the kitchen, carrying three carrier bags and a cardboard box and calling, “Coo-ee! It’s me!” When she arrived in the living room, she sank down into the striped armchair and panted, “I just had to come in. I’m on my way to the Community Hall, but my feet are killing me. I’ve been all afternoon collecting prizes for the party for the Society for Underprivileged Children on Saturday – I must have walked miles! But you wouldn’t believe what wonderful prizes people have given me. Just look.” She dumped her cardboard box on the arm of the chair – it was the arm with the ink blot – in order to fetch a bright green teddy bear out of one of the carrier bags. She wagged the teddy in their faces. “Isn’t he charming?”

“So-so,” said Dad and Marcia added, “Perhaps he’d look better without the pink ribbon.” Simon and Mum were too polite to say anything.

“And here’s such a lovely clockwork train!” Auntie Christa said, plunging the teddy back in the bag and pulling out a broken engine. “Isn’t it exciting? I can’t stay long enough to show you everything – I have to go and see to the music for the Senior Citizens’ Dance in a minute – but I think I’ve just got time to drink a cup of tea.”

“Of course,” Mum said guiltily. “Coming up.” She dashed into the kitchen.

Auntie Christa was good at getting people to do things. She was a very busy lady. Whatever went on at the Community Hall – whether it was a Youth Club Disco, Children’s Fancy Dress competition, Dog Training, Soup for the Homeless or a Jumble Sale – Auntie Christa was sure to be in the midst of it, telling people what to do. She was usually too busy to listen to what other people said. Mum said Auntie Christa was a wonder, but Dad quite often muttered, “Quack-quack-quack,” under his breath when Auntie Christa was talking.

“Quack-Quack,” Dad murmured as Auntie Christa went on fetching things out of her bags and telling them what good prizes they were. Auntie Christa had just got through all the things in the bags and was turning to the cardboard box on the arm of the chair, when Mum came dashing back with tea and biscuits.

“Tea!” Auntie Christa said. “I can always rely on a cup of tea in this house!”

She turned gladly to take the tea. Behind her, the box slid into the chair.

“Never mind,” said Auntie Christa. “I’ll show you what’s in there in a minute. It will thrill Simon and Marcia – oh, that reminds me! The Africa Aid Coffee Morning has to be moved this Saturday because the Stamp Collectors need the hall. I think we’ll have the coffee morning here instead. You can easily manage coffee and cakes for twenty on Saturday, can’t you?” she asked Mum. “Marcia and Simon can help you.”

“Well—” Mum began, while Dad looked truly dismayed.

“That’s settled, then,” said Auntie Christa and quickly went on to talk about other things. Dad and Simon and Marcia looked at one another glumly. They knew they were booked to spend Saturday morning handing round cakes and soothing Mum while she fussed. But it was worse than that.

“Now, you’ll never guess what’s in the box,” Auntie Christa said, cheerily passing her cup for more tea. “Suppose we make it a competition. Let’s say that whoever guesses wrong has to come and help me with the Underprivileged Children’s Society party on Saturday afternoon.”

“I think we’ll all be busy—” Dad tried to say.

“No refusing!” Auntie Christa cried. “People are so wicked, the way they always try to get out of doing good deeds! You can have one guess each. And I’ll give you a clue. Old Mr Pennyfeather gave me the box.”

As old Mr Pennyfeather kept the junk shop, there could have been almost anything in the box. They all thought rather hard.

Simon thought the box had rattled as it tipped. “A tea-set,” he guessed.

Marcia thought she had heard the box slosh. “A goldfish in a bowl,” she said.

Mum thought of something that might make a nice prize and guessed, “Dolls’ house furniture.”

Dad thought of the sort of things that were usually in Mr Pennyfeather’s shop and said, “Mixed-up jigsaws.”

“You’re all wrong, of course!” Auntie Christa said while Dad was still speaking. She sprang up and pulled the box back to the arm of the chair. “It’s an old-fashioned conjurer’s kit. Look. Isn’t it thrilling?” She held up a large black top hat with a big shiny blue ball in it. Water – or something – was dripping out of the hat underneath. “Oh dear,” Auntie Christa said. “I think the crystal ball must be leaking. It’s made quite a puddle in your chair.”

Dark liquid was spreading over the seat of the chair, mixing with the old ketchup stain.

“Are you sure you didn’t spill your tea?” Dad asked.

Mum gave him a stern look. “Don’t worry,” she said. “We were going to throw the chair away, anyway. We were just talking about it when you came.

“Oh good!” Auntie Christa said merrily. She rummaged in the box again. “Look, here’s the conjurer’s wand,” she said, bringing out a short white stick wrapped in a string of little flags. “Let’s magic the nasty wet away

so that I can sit down again.” She tapped the puddle in the chair with the stick. “There!”

“The puddle hasn’t gone,” said Dad.

“I thought you were going to throw the hideous old thing away, anyway,” Auntie Christa said crossly. “You should be quite ashamed to invite people for a coffee morning and ask them to sit in a chair like this!”

“Then perhaps,” Dad said politely, “you’d like to help us carry the chair outside to the garden shed?”

“I’d love to, of course,” Auntie Christa said, hurriedly putting the hat and the stick back into the box and collecting her bags, “but I must dash. I have to speak to the vicar before I see about the music. I’ll see you all at the Underprivileged Children’s Society party the day after tomorrow at four-thirty sharp. Don’t forget!”

This was a thing Simon and Marcia had often noticed about Auntie Christa. Though she was always busy, it was always other people who did the hard work.

ow Mum had told Auntie Christa they were going to throw the chair away, she wanted to do it at once.

“We’ll go and get another one tomorrow after work,” she told Dad. “A nice blue, I think, to go with the curtains. And let’s get this one out of the way now. I’m sick of the sight of it.”

It took all four of them to carry the chair through the kitchen to the back door, and they knocked most of the kitchen chairs over doing it. For the next half hour they thought they were not going to get it through the back door. It stuck, whichever way they tipped it. Simon was quite upset. It was almost as if the chair was trying to stop them throwing it away. But they got it into the garden in the end. Somehow, as they staggered across the lawn with it, they knocked the top off Mum’s new sundial and flattened a rosebush. Then they had to stand it sideways in order to wedge it inside the shed.

“There,” Dad said, slamming the shed door and dusting his hands. “That’s out of the way until Guy Fawkes Day.”

He was wrong, of course.

The next day, Simon and Marcia had to collect the key from next door and let themselves into the house, because Mum had gone straight from work to meet Dad and buy a new chair. They felt very gloomy being in the empty house. The living room looked queer with an empty space where the chair had been. And b

oth of them kept remembering that they would have to spend Saturday helping in Auntie Christa’s schemes.

“Handing round cakes might be fun,” Simon said doubtfully.

“But helping with the party won’t be,” said Marcia. “We’ll have to do all the work. Why couldn’t one of us have guessed what was in that box?”

“What are Underprivileged Children, anyway?” asked Simon.

“I think,” said Marcia, “that they may be the ones who have to let themselves into their houses with a key after school.”

They looked at one another. “Do you think we count?” said Simon. “Enough to win a prize, anyway. I wouldn’t mind winning that conjuring set. It was a real top hat, even if the crystal ball did leak.”

Here they both began to notice a distant thumping noise from somewhere out in the garden. It suddenly felt unsafe being alone in the house.

“It’s only next door hanging up pictures again,” Marcia said bravely.

But when they went rather timidly to listen at the back door, the noise was definitely coming from the garden shed.

“It’s next door’s dog got shut in the shed again,” Simon said. It was his turn to be brave. Marcia was scared of next door’s dog. She hung back while Simon marched over the lawn and tugged and pulled until he got the shed door open.

It was not a dog. There was a person standing inside the shed. The person stood and stared at them with his little head on one side. His little fat arms waved about as if he was not sure what to do with them. He breathed in heavy snorts and gasps as if he was not sure how to breathe.

“Er, hn hm,” he said as if he was not sure how to speak either. “I appear to have been shut in your shed.”

“Oh – sorry!” Simon said, wondering how it had happened.

The person bowed, in a crawlingly humble way. “I – hn hm – am the one who is snuffle sorry,” he said. “I have made – hn hm – you come all the way here to let me out.” He walked out of the shed, swaying from foot to foot.

Simon backed away, wondering if the person walked like that because he had no shoes on. He was a solid, plump person with wide, hairy legs. He was wearing a most peculiar striped one-piece suit that only came to his knees.

Marcia backed away behind Simon, staring at the person’s stripy arms. He waved them about in a feeble way as he walked. There was a blot of ink on one arm and what looked like a coffee stain on the other. Marcia’s eyes went to the person’s plump striped stomach. As he came out into the light, she could see that the stripes were sky-blue, orange and purple. There was a damp patch down the middle and a dark sticky place that could have been ketchup, once. Her eyes went up to his sideways face. There was a beard on the person’s chin that looked rather as if someone had smashed a hedgehog on it.

“Who are you?” she said.

The person stood still. His arms waved like seaweed in a current. “Er, hn hm, I am Chair Person,” he said. His sideways face looked pleased and rather smug about it.

Marcia and Simon of course both felt awful about it. He was the armchair. They had put him in the shed ready to go on the bonfire. Now he was alive. They hoped very much that Chair Person did not know that they had meant to burn him.

“Won’t you come inside?” Simon said politely.

“That is very kind of you,” Chair Person said, crawlingly humble again. “I – hn hm snuffle – hope that won’t be too much trouble.”

“Not at all!” they both said heartily.

They went towards the house. Crossing the lawn was quite difficult, because Chair Person did not seem to have learnt to walk straight yet, and he talked all the time. “I believe I am – hn hm – Chair Person,” he said, crashing into what was left of the sundial and knocking it down, “because I think I am. Snuffle. Oh dear, I appear to have destroyed your stone pillar.”

“Not to worry,” Marcia said kindly. “It was broken last night when we – I mean, it was broken anyway.”

“Then – hn hm – as I was saying,” Chair Person said, veering the other way, “that this is what snuffle wise men say. A person who thinks is a Person.” He cannoned into the apple tree. Most of the apples Dad had meant to pick that weekend came showering and bouncing down on to the grass. “Oh dear,” said Chair Person. “I appear to have loosened your fruit.”

“That’s all right,” Simon and Marcia said politely. But since Chair Person, in spite of seeming so humble, did not seem very sorry about the apples and just went on talking and weaving about, they each took hold of one of his waving arms and guided him to the back door.

“Only the finest snuffle apples,” said Chair Person as he bashed into both sides of the back door, “from the finest – hn hm – orchards go into Smith’s Family Apple Pies. This is one of many snuffle facts I know. Er, hm, very few people have watched as much television as I have,” he added, knocking over the nearest kitchen chair.

Marcia picked the chair up, thinking of the many, many times she had gone out of the living room and forgotten to turn the television off. Chair Person, when he was an armchair, must have watched hours of commercials and hundreds of films.

Simon turned Chair Person round and sat him in the kitchen chair. Chair Person went very humble and grateful. “You are – hn hm – treating me with such kindness,” he said, “and I am going to cause you a lot of snuffle trouble. I appear to need something to eat. I am not sure what to do about it. Do I – hn hm – eat you?”

“We’ll find you something to eat,” Simon said quickly.

“Eating people is wrong,” Marcia explained.

They hurried to find some food. A tin of spaghetti seemed easiest, because they both knew how to do that. Simon opened the tin and Marcia put it in a saucepan with the gas very high to get the spaghetti hot as soon as possible. Both of them cast nervous looks at Chair Person in case he tried to eat one of them. But Chair Person sat where he was, waving his arms gently. “Hn hm, Spiggley’s tasty snacks,” he said. “Sunshine poured from a tin.” When Marcia put the steaming plateful in front of him and Simon laid a spoon and a fork on either side of it, Chair Person went on sitting and staring.

“You can eat it,” Simon said kindly.

“Er, hn hm,” Chair Person said. “But this is not a complete meal. I shall have to trouble you for a napkin and salt and pepper. And I think people usually snuffle eat by candle light with soft music in the background.”

They hurried to find him the salt, the pepper mill and a paper towel. Simon fetched the radio and turned it on. It was playing Country and Western, but Simon turned it down very low and hoped it would do. He felt so sorry for Chair Person that he wanted to please him. Marcia ran upstairs and found the candlesticks from Mum’s dressing table and two red candles from last Christmas. She felt so guilty about Chair Person that she wanted to please him as much as Simon did.

Chair Person was very humble and grateful. While he told them how kind they were being, he picked up the pepper mill and began solemnly grinding pepper over the spaghetti. “Er, hn hm, with respect to you two fine kind people,” he said as he ground, “eating people is a time-honoured custom.”

Simon and Marcia quickly got to the other side of the table. But Chair Person only took the fork and raked the spaghetti into a new heap, and ground more pepper over that. “There were tribes in South snuffle America,” he said, “who believed it was quite correct to – hn hm – eat their grandparents. I have a question. Is Spiggley’s another word for spaghetti?”

“No,” said Marcia. “It’s a name.”

Chair Person raked the spaghetti into a different-shaped heap and went on grinding pepper over it. “When the snuffle grandparents were dead,” he said, “they cooked the grandparents and the whole tribe had a feast.”

Marcia remembered seeing something like this on television. “I watched that programme too,” she said.

“You – hn hm – will not know this,” Chair Person said, raking the spaghetti into another new shape and grinding another cloud of pepper over it. �

��Only the sons and daughters of the dead men were allowed to eat the brains.” This time he spread the spaghetti flat and ground pepper very carefully over every part of it. “This was so that snuffle the wisdom of the dead man could be passed on to his family,” he said.

By this time the spaghetti was grey. Simon and Marcia could not take their eyes off it. It must have been hot as fire by then. They kept expecting Chair Person to sneeze, since he seemed to have trouble breathing anyway, but he just went on grinding pepper and explaining about cannibals.

Simon wondered if Chair Person perhaps did not know how to eat. “You’re supposed to put the spaghetti in your mouth,” he said.

Chair Person held up the pepper mill and shook it. It was empty. So he put it down at last and picked up the spoon. He did seem to know how to eat, but he did it very badly, snuffling and snorting, with ends dangling out of his mouth. Grey juice dripped through his smashed-hedgehog beard and ran down his striped front. But the pepper did not seem to worry him at all. Simon was thinking that maybe Chair Person did not have taste buds like other people, when the back door opened and Mum and Dad came in.

“What happened to the rest of the sundial?” said Mum. “I leave you alone just for—” She saw Chair Person and stared.

“What have you kids done to those apples?” Dad began. Then he saw Chair Person and stared too.

oth Simon and Marcia had had a sort of hope that Chair Person would vanish when Mum and Dad came home, or at least turn back into an armchair. But nothing of the sort happened. Chair Person stood up and bowed.

“Er, hn hm,” he said. “I am Chair Person. Good snuffle evening.”

Mum’s eyes darted to the ink blot on Chair Person’s waving sleeve, then to the coffee stain, and then on to the damp smear on his front. She turned and dashed away into the garden.

Chair Person’s arms waved like someone conducting an orchestra. “I am the one causing you all this trouble with your apples,” he said, in his most crawlingly humble way. “You are so kind to – hn hm – forgive me so quickly.”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

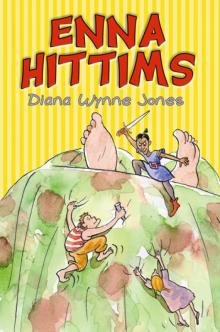

Reflections Enna Hittms

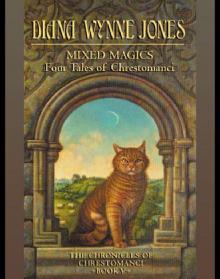

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci