- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

Stopping for a Spell Page 3

Stopping for a Spell Read online

Page 3

While they argued, Auntie Christa was leading the coffee morning people in a rush to escape through the kitchen and out of the back door. “I do think,” the Vicar said kindly to Mum as he scampered past, “that your eccentric uncle would be far happier in a Home, you know.”

Mum waited until the last person had hurried through the back door. Then she burst into tears. Simon did not know what to do. He stood staring at her. “A Home!” Mum wept. “I’m the one who’ll be in a Home if someone doesn’t do something!”

5

Junk Shop

Chair Person got his way over the new chair, more or less. The men carried it to the garden shed and shoved it inside. Then they left, looking almost as bewildered and angry as Dad.

Marcia, watching and listening, was quite sure now that Chair Person had been learning from Auntie Christa all these years. He knew just how to make people do what he wanted. But Auntie Christa did not live in the house. You could escape from her sometimes. Chair Person seemed to be here to stay.

“We’ll have to get him turned back into a chair somehow,” she said to Simon. “He’s not getting better. He’s getting worse and worse.”

Simon found he agreed. He was not sorry for Chair Person at all now. “Yes, but how do we turn him back?” he said.

“We could ask old Mr. Pennyfeather,” Marcia suggested. “The conjuring set came from his shop.”

So that afternoon they left Mum lying on her bed upstairs and Dad moodily picking up frostbitten apples from the grass. Chair Person was still eating lunch in the kitchen.

“Where does he put it all?” Marcia wondered as they hurried down the road.

“He’s a chair. He’s got lots of room for stuffing,” Simon pointed out.

Then they both said, “Oh, no!”

Chair Person was blundering up the road after them, panting and snuffling and waving his arms. “Er, hn hm, wait for me!” he called out. “You appear to have snuffle left me behind.”

He tramped beside them, looking pleased with himself. When they got to the shops where all the people were, shoppers turned to stare as Chair Person clumped past in Dad’s shoes. Their eyes went from the shoes, to the football socks, and then to the short, striped suit, and then on up to stare wonderingly at the smashed-hedgehog beard. More heads turned every time Chair Person’s voice brayed out, and of course, he talked a lot. There was something in every shop to set him going.

At the bread shop he said, “Er, hn hm, those are Sam Browne’s lusty loaves. I happen to know snuffle they are nutrition for the nation.”

Outside the supermarket he said, “Cheese to please, you can snuffle freeze it, squeeze it and—er, hn hm—there is Tackley’s tea, which I happen to know has over a thousand holes to every bag. Flavor to snuffle savor.”

Outside the wine shop his voice went up to a high roar. “I—hn hm—see Sampa’s Superb sherry here, which is for ladies who like everything silken snuffle smooth. And I happen to know that in the black bottle there is—hn hm—a taste of Olde England. There is a stagecoach on the—hn hm—label to prove it. And look, there is Bogans—hn hm—beer, which is, of course, for Men Only.”

By now it seemed to Simon and Marcia that everyone in the street was staring. “You don’t want to believe everything the ads say,” Simon said uncomfortably.

“Er, hn hm, I appear to be making you feel embarrassed,” Chair Person brayed, louder than ever. “Just tell me snuffle if I am in your way and I will snuffle go home.”

“Yes, do,” they both said.

“I—er, hn hm—wouldn’t dream of pushing in where I am snuffle not wanted,” Chair Person said. “I would—hn hm—count it a favor if you tell me snuffle truthfully every time you’ve had enough of me. I—er, hn hm—know I must bore you quite often.”

By the time he had finished saying this they had arrived at old Mr. Pennyfeather’s junk shop. Chair Person stared at it.

“We—er, hn hm—don’t need to go in there,” he said. “Everything in it is old.”

“You can stay outside then,” said Marcia.

But Chair Person went into another long speech about not wanting to be—hn hm—a trouble to them and followed them into the shop. “I—er, hn hm—might get lost,” he said, “and then what would you do?”

He bumped into a cupboard.

Its doors opened with a clap, and a stream of horse brasses poured out: clatter, clatter, CLATTER!

Chair Person lurched sideways from the horse brasses and walked into an umbrella stand made out of an elephant’s foot,

which fell over—crash CLATTER—

against a coffee table with a big jug on it,

which tipped and slid the jug off—CRASH, splinter, splinter—

and then fell against a rickety bookcase,

which collapsed sideways, spilling books—thump, thump, thump-thump-thump—

and hit another table loaded with old magazines and music,

which all poured down around Chair Person.

It was like dominoes going down.

The bell at the shop door had not stopped ringing before Chair Person was surrounded in knocked-over furniture and knee-deep in old papers. He stood in the midst of them, waving his arms and looking injured.

By then Mr. Pennyfeather was on his way from the back of the shop, shouting, “Steady, steady, steady!”

“Er, hn hm—er, hn hm,” said Chair Person, “I appear to have knocked one or two things over.”

Mr. Pennyfeather stopped and looked at him, in a knowing, measuring kind of way. Then he looked at Simon and Marcia. “He yours?” he said. They nodded. Mr. Pennyfeather nodded, too. “Don’t move,” he said to Chair Person. “Stay just where you are.”

Chair Person’s arms waved as if he were conducting a very large orchestra, several massed choirs, and probably a brass band or so as well. “I—er, hn hm, er, hn hm—I—er, hn hm—” he began.

Mr. Pennyfeather shouted at him, “Stand still! Don’t move, or I’ll have the springs out of you and straighten them for toasting forks! It’s the only language they understand,” he said to Simon and Marcia. “STAND STILL! YOU HEARD ME!” he shouted at Chair Person.

Chair Person stopped waving his arms and stood like a statue, looking quite frightened.

“You two come this way with me,” said Mr. Pennyfeather, and he took Simon and Marcia down to the far end of his shop, between an old ship’s wheel and a carved maypole, where there was an old radio balanced on a tea chest. He turned the radio up loud so that Chair Person could not hear them. “Now,” he said, “I see you two got problems to do with that old conjuring set. What happened?”

“It was Auntie Christa’s fault,” said Marcia.

“She let the crystal ball drip on the chair,” said Simon.

“And tapped it with the magic wand,” said Marcia.

Mr. Pennyfeather scratched his withered old cheek. “My fault, really,” he said. “I should never have let her have those conjuring things, only I’d got sick of the way the stuff in my shop would keep getting lively. Tables dancing and such. Mind you, most of my furniture only got a drip or so. They used to calm down after a couple of hours. That one of yours looks as though he got a right dousing—or maybe the wand helped. What was he to begin with, if you don’t mind my asking?”

“Our old armchair,” said Simon.

“Really?” said Mr. Pennyfeather. “I’d have said he was a sofa, from the looks of him. Maybe what you had was an armchair with a sofa opinion of itself. That happens.”

“Yes, but how can we turn him back?” said Marcia.

Mr. Pennyfeather scratched his withered cheek again. “This is it,” he said. “Quite a problem. The answer must be in that conjuring set. It wouldn’t make no sense to have that crystal ball full of stuff to make things lively without having the antidote close by. That top hat never got lively. You could try tapping him with the wand again. But you’d do well to sort through the box and see if you couldn’t come up with whatever was put on the top h

at to stop it getting lively at all.”

“But we haven’t got the box,” said Simon. “Auntie Christa’s got it.”

“Then you’d better borrow it back off her quick,” Mr. Pennyfeather said, peering along his shop to where Chair Person was still standing like a statue. “Armchairs with big opinions of theirselves aren’t no good. That one could turn out a real menace.”

“He already is,” said Simon.

Marcia took a deep, grateful breath and said, “Thanks awfully, Mr. Pennyfeather. Do you want us to help tidy up your shop?”

“No, you run along,” said Mr. Pennyfeather. “I want him out of here before he does any worse.” And he shouted down the shop at Chair Person, “Right, you can move now! Out of my shop at the double, and wait in the street!”

Chair Person nodded and bowed in his most crawlingly humble way and waded through the papers and out of the shop. Simon and Marcia followed, wishing they could manage to shout at Chair Person the way Mr. Pennyfeather had. But maybe they had been brought up to be too polite. Or maybe it was Chair Person’s sofa opinion of himself. Or maybe it was just that Chair Person was bigger than they were and had offered to eat them when he first came out of the shed. Whatever it was, all they seemed to be able to do was to let Chair Person clump along beside them, talking and talking, and try to think how to turn him into a chair again.

They were so busy thinking that they had turned into their own road before they heard one thing that Chair Person said. And that was only because he said something new.

“What did you say?” said Marcia.

“I said,” said Chair Person, “I appear—er, hn hm, snuffle—to have set fire to your house.”

Both their heads went up with a jerk. Sure enough, there was a fire engine standing in the road by their gate. Firemen were dashing about unrolling hoses. Thick black smoke was rolling up from behind the house, darkening the sunlight and turning their roof black.

Simon and Marcia forgot Chair Person and ran.

Mum and Dad, to their great relief, were standing in the road beside the fire engine, along with most of the neighbors. Mum saw them. She let go of Dad’s arm and rushed up to Chair Person.

“All right. Let’s have it,” she said. “What did you do this time?”

Chair Person made bowing and hand-waving movements, but he did not seem sorry or worried. In fact, he was looking up at the surging clouds of black smoke rather smugly. “I—er, hn hm—was thirsty,” he said. “I appear to have drunk all your orange juice and lemon squash and the stuff snuffle from the wine and whiskey bottles, so I—hn hm—put the kettle on the gas for a cup of tea. I appear to have forgotten it when I went out.”

“You fool!” Mum screamed at him. “It was an electric kettle, anyway!” She was angry enough to behave just like Mr. Pennyfeather. She pointed a finger at Chair Person’s striped stomach. “I’ve had enough of you!” she shouted. “You stand there and don’t dare move! Don’t stir, or I’ll—I’ll—I don’t know what I’ll do, but you won’t like it!”

And it worked, just as it did when Mr. Pennyfeather shouted. Chair Person stood still as an overstuffed statue. “I—hn hm—appear to have annoyed you,” he said in his most crawlingly humble way.

He stood stock-still in the road all the time the firemen were putting out the fire. Luckily only the kitchen was burning. Dad had seen the smoke while he was picking up apples in the garden. He had been in time to phone the fire brigade and get Mum from upstairs before the rest of the house caught fire. The firemen hosed the blaze out quite quickly. Half an hour later Chair Person was still standing in the road and the rest of them were looking around the ruined kitchen.

Mum gazed at the melted cooker, the crumpled fridge, and the charred stump of the kitchen table. Everything was black and wet. The vinyl floor had bubbled. “Someone get rid of Chair Person,” Mum said, “before I murder him.”

“Don’t worry. We’re going to,” Simon said soothingly.

“But we have to go and help at Auntie Christa’s children’s party in order to do it,” Marcia explained.

“I’m not going,” Mum said. “There’s enough to do here—and I’m not doing another thing for Auntie Christa—not after this morning!”

“Even Auntie Christa can’t expect us to help at her party after our house has been on fire,” Dad said.

“Simon and I will go,” Marcia said. “And we’ll take Chair Person and get him off your hands.”

6

Party Games

The smoke had made everything in the house black and gritty. Simon and Marcia could not find any clean clothes, but the next-door neighbors let them use their bathroom and kindly shut up their dog so that Marcia would not feel nervous. The neighbors on the other side invited them to supper when they came back. Everyone was very kind. More kind neighbors were standing anxiously around Chair Person when Simon and Marcia came to fetch him. Chair Person was still standing like a statue in the road.

“Is he ill?” the lady from Number 27 asked.

“No, he’s not,” Marcia said. “He’s just eccentric. The vicar says so.”

Simon did his best to imitate Mr. Pennyfeather. “Right,” he barked at Chair Person. “You can move now. We’re going to a party.”

Though Simon sounded to himself just like a nervous person talking loudly, Chair Person at once started snuffling and waving his arms about. “Oh—hn hm—good,” he said. “I believe I shall like a party. What snuffle party is it? Conservative, Labour, or that party whose name keeps changing? Should I be—hn hm—sick of the moon or over the parrot?”

At this, all the neighbors nodded to one another. “Very eccentric,” the lady from Number 27 said as they all went away.

Simon and Marcia led Chair Person toward the Community Hall trying to explain that it was a party for Caring Society Children. “And we’re supposed to be helping,” Marcia said. “So do you think you could try to behave like a proper person for once?”

“You—hn hm—didn’t have to say that!” Chair Person said. His feelings were hurt. He followed them into the hall in silence.

The hall was quite nicely decorated with bunches of balloons and full of children. Simon and Marcia knew most of the children from school. They were surprised they needed caring for, most of them seemed just ordinary children. But the thing they looked at mostly was the long table at the other end of the room. It had a white cloth on it. Much of it was covered with food: jellies, cakes, crisps, and big bottles of Coke. But at one end was the pile of prizes, with the green teddy on top. The conjuring set, being quite big, was at the bottom of the pile. Simon and Marcia were glad, because that would mean it would be the last prize anybody won. They would have time to look through the box.

Auntie Christa was in the midst of the children, trying to pin someone’s torn dress. “There you are at last!” she called to Simon and Marcia. “Where are your mother and father?”

“They couldn’t come—we’re awfully sorry!” Marcia called back.

Auntie Christa rushed out from among the children. “Couldn’t come? Why not?” she said.

“Our house has been on fire—” Simon began to explain.

But Auntie Christa, as usual, did not listen. “I think that’s extremely thoughtless of them!” she said. “I was counting on them to run the games. Now I shall have to run them myself.”

While they were talking, Chair Person lumbered into the crowd of children, waving his arms importantly. “Er, hn hm, welcome to the party,” he brayed. “You are all honored to have me here because I am—snuffle—Chair Person and you are only children who need caring for.”

The children stared at him resentfully. None of them thought of themselves as needing care. “Why is he wearing football socks?” someone asked.

Auntie Christa whirled around and stared at Chair Person. Her face went quite pale. “Why did you bring him?” she said.

“He—er—he needs looking after,” Marcia said, rather guiltily.

“He just nea

rly burned our house down,” Simon tried to explain again.

But Auntie Christa did not listen. “I shall speak to your mother very crossly indeed!” she said, and ran back among the children, clapping her hands. “Now listen, children. We are going to play a lovely game. Stand quiet while I explain the rules.”

“Er, hn hm,” said Chair Person. “There appears to be a feast laid out over there. Would it snuffle trouble you if I started eating it?”

At this, quite a number of the children called out, “Yes! Can we eat the food now?”

Auntie Christa stamped her foot. “No, you may not! Games come first. All of you stand in a line, and Marcia, bring those beanbags from over there.”

Once Auntie Christa started giving orders, Chair Person became quite obedient. He did his best to join in the games. He was hopeless. If someone threw him a beanbag, he dropped it. If he threw a beanbag at someone else, it hit the wall or threatened to land in a jelly. The team he was in lost every time.

So Auntie Christa tried team Follow My Leader, and that was even worse. Chair Person lost the team he was with and galumphed around in small circles on his own. Then he noticed that everyone was running in zigzags and ran in zigzags, too. He zagged when everyone else zigged, bumping into people and treading on toes.

“Can’t you stop him? He’s spoiling the game!” children kept complaining.

Luckily Chair Person kept drifting off to the table to steal buns or help himself to a pint or so of Coke. After a while Auntie Christa stopped rounding him up back into the games. It was easier without him.

But Simon and Marcia were getting worried. They were being kept so busy helping with teams and fetching things and watching in case people cheated that they had no time at all to get near the conjuring set. They watched the other prizes go. The green teddy went first, then the broken train, and then other things, until half the pile was gone.

Then at last Auntie Christa said the next game was Musical Chairs. “Simon and Marcia will work the record player, and I’ll be the judge,” she said. “All of you bring one chair each into the middle. And you!” she said, grabbing Chair Person away from where he was trying to eat a jelly. “This is a game even you can play.”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

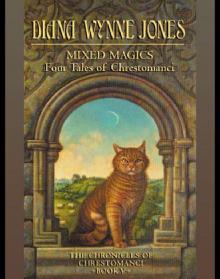

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

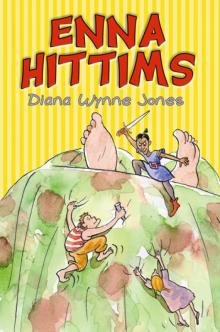

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci