- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

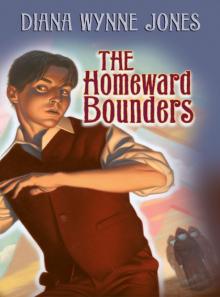

The Homeward Bounders Page 3

The Homeward Bounders Read online

Page 3

On this first occasion, Mrs. Chief sent two hairy riders after me and they rounded me up just like a cow.

“What do you think you’re doing, going off on your own like that?” she screamed at me. “Suppose you meet an enemy!”

“First I heard you had any enemies,” I said sulkily. The pulling and the yearning were terrible.

She made me ride in the middle of the girls after that, and wouldn’t listen to anything I said. I’ve learned to hold my tongue when the Bounds call now. It saves trouble. Then, I had to wait till night came, and it was agony. I felt pulled out of shape by the pull and sick with the longing—really sick: I couldn’t eat supper. Waste of a good beef steak. Worse still, I was all along haunted by the idea I was going to be too late. I was going to miss my chance of getting Home. I had to get to some particular place in order to move to other worlds, and I wasn’t going to get there in time.

It was quite dark when at last I got the chance to slip away. It was a bit cloudy and there was no moon—some worlds don’t have moons: others have anything up to three—but that didn’t matter to me. The Bounds called so strongly that I knew exactly which way to head. I went that way at a run. I ran all through the warm moisty night. I was drowned in sweat and panting like someone sawing wood. In the end, I was falling down every few yards, getting up again, and staggering on. I was so scared I’d be too late. By the time the sun rose, I think I was simply going from one foot to the other, almost on the spot. Stupid. I’ve learned better since. But this was the first time, and, when there was light, I shouted out with joy. There was a green flat space among the green hills ahead, and someone had marked the space with a circle of wooden posts.

At that, I managed to trot and lumbered into the circle. Somewhere near the middle of it, the twitch took me sideways again.

You’ve probably guessed what happened. You can imagine how I felt anyway. It was dawn still, a lurid streaky dawn. The green ranges had gone, but there was no city—nothing like one. The bare lumpy landscape round me was heaped with what looked like piles of cinders, and each pile had its own dreary little hut standing beside it. I had no idea what they were—they were mines, actually. You weren’t a person in that new world if you didn’t have your own hole and keep digging coal or copper out of it. But I didn’t care what was going on. I was feeling the air, as I did before, and realizing that this was yet another different world. And at the same time, I realized that I was due to stay here for rather a long time.

It was on this world that I began to understand that They hadn’t told me even half the rules. They had just told me the ones that interested Them. On this world I was starved and hit, and buried under a collapsed slag-heap. I’m not going to describe it. I hate it too much. I was there twice too, because what happened was that I got caught in a little ring of worlds and went all round the ring two times. At the time, I thought they were all the worlds there were—except for Home, which I never seemed to get to—and I thought of them as worlds, which they are not, not really.

They are separate universes, stacked in together like I saw the triangular rooms of Them before They sent me off. These universes all touch somewhere—and where they touch is the Boundary—but they don’t mix. Homeward Bounders seem to be the only people who can go from one universe to another. And we go by walking the Bounds until we come to a Boundary, when, if one of Them has finished his move, we get twitched into the Boundary in another Earth, in another universe. I only understood this properly when I got to the sixth world round, where the stars are all different.

I looked at those stars. “Jamie boy,” I said. “This is crazy.” Possibly I was a little crazy then, too, because Jamie answered me, and said, “They’re probably the stars in the Southern hemisphere—Australia and all that.” And I answered him. “It’s still crazy,” I said. “This world’s upside down then.”

It was upside down, in more ways than that. The Them that played it must have been right peculiar. But it was that which made me feel how separate and—well—universal each world was. And how thoroughly I was a discard, a reject, wandering through them all and being made to move on all the time. For a while after that, I went round seeing all worlds as nothing more than colored lights on a wheel reflected on a wall. They are turning the wheel and lighting the lights, and all we get is the reflections, no more real than that. I still see it that way sometimes. But when you get into a new world, it’s as solid as grass and granite can make it, and the sky shuts you in just as if there was no way through. Then you nerve yourself up. Here comes the grind of finding out its ways and learning its language.

You wouldn’t believe how lonely you get.

But I was going to tell you about the rules that They didn’t tell me. I mentioned some of the trouble I had in the mining world. I had more in other worlds. And none of these things killed me. Some of them ought to have done, specially that slag-heap—I was under it for days. And that is the rule: call it Rule One. A random factor like me, walking the Bounds, has to go on. Nothing is allowed to stop him. He can starve, fall off a mile-high temple, get buried, and still he goes on. The only way he can stop is to come Home.

People can’t interfere with a Homeward Bounder either. That may be part of Rule One, but I prefer to call it Rule Two. If you don’t believe people can’t interfere with me, find me and try it. You’ll soon see: I’ll tell you—on my fifth world, I had a little money for once. A whole gold piece, to be precise. I got an honest job in a tannery—and carried the smell right through to the next world with me too. On my day off, I was strolling in the market looking for my favorite cakes. They were a little like Christmas puddings with icing on—gorgeous! Next thing I knew, a boy about my own age had come up beside me, given me a chop-and, chop-and—it darned well hurt too—and run off with my gold piece. Naturally, I yelled and started to run after him. But he was under a wagon the next moment, dead as our neighbor’s little girl back Home. His hand with the gold piece in it was sticking out, just as if he was handing it back to me, but I hadn’t the heart to take it. I couldn’t. It felt like my fault, that wagon.

After a while, I told myself I was imagining that rule. That boy’s corpse could have had a bad effect on play, just as They said mine would have done. But I think that was one of the things They meant by the risk adding to the fun. I didn’t imagine that rule. The same sort of thing happened to me several times later on. The only one I didn’t feel bad about was a rotten Judge who was going to put me in prison for not being able to bribe him. The roof of the courthouse fell in on him.

Rule Three isn’t too good either. Time doesn’t act the same in any world. It sort of jerks about as you go from one to another. But time hardly acts at all on a Homeward Bounder. I began to see that rule on my second time round the circle of worlds. The second time I got to the upside down one, for instance, nearly ten years had gone by, but only eight or so when I got to the next one. I still don’t know how much of my own time I spent going round that lot, but I swear I was only a few days older. It seemed to me I had to be keeping the time of my own Home. But, as I told you, I still only seem about thirteen years old, and I’ve been on a hundred worlds since then.

By the time I had all this worked out, I was well on my second round of the circle. I had learned I wasn’t going to get Home anything like as easily as I had thought. Sometimes I wondered if I was ever going to get there. I went round with an ache like a cold foot inside me over it. Nothing would warm that ache. I tried to warm it by remembering Home, and our courtyard and my family, in the tiniest detail. I remembered things I had not really noticed when they happened—silly things, like how particular our mother was over our boots. Boots cost a lot. Some of the kids in the court went without in summer, and couldn’t play football properly, but we never went without. If my mother had to cut up her old skirt to make Elsie a dress in order to afford them, we never went without boots. And I used to take that for granted. I’ve gone barefoot enough since, I can tell you.

And I remem

bered even the face Elsie used to make—she sort of pushed her nose down her face so that she looked like a camel—when Rob’s old boots were mended for her to wear. She never grumbled. She just made that face. I remember my father made a bit the same face when my mother wanted me to stay on at school. I swore to myself that I’d help him out in the shop when I did get Home. Or go grinding on at school, if that was what they decided. I’d do anything. Besides, after grinding away learning languages the way I’d done, school might almost seem lively.

I think remembering that way made the cold foot ache inside me worse, but I couldn’t stop. It made me hate Them worse too, but I didn’t mind that.

All this while, I’d never met a single other Homeward Bounder. I thought that was a rule too, that we weren’t supposed to. I reckoned that we were probably set off at regular intervals, so that we never overtook one another. I knew there were others, of course. After a bit, I learned to pick up traces of them. We left signs for one another—like tramps and robbers do in some worlds—mostly at Boundaries.

It took me a long while to work the signs out, on my own. For one thing, the Boundaries varied so much, that I didn’t even notice the signs until I’d learned to look for them. The ring of posts in the cattle-range world matched with a clump of trees in the fourth world, and with a dirty great temple in the seventh. In the mining world, there was nothing to mark the Boundary at all. Typical, that. I used to think that They had marked the Boundaries with these things, and I got out of them quick at first, until I noticed the sign carved on one of the trees. Somehow that made me feel that the people on the worlds must have marked the Boundaries. There was the same sign carved in the temple too. This sign meant GOOD PICKINGS. I earned good money in both worlds.

Then, by the time I was going round the whole collection another time, I was beginning to get the hang of the Bounds too, as well as the signs and the Boundaries. Bounds led into the Boundary from three different directions, so you could come up by another route and still go through the Boundary, but from another side. I saw more signs that way. But a funny thing was that the ordinary people in the worlds seemed to know the Bounds were there, as well as the Boundaries. They never walked the Bounds of course—they never felt the call—but they must have felt something. In some worlds there were towns and villages all along a Bound. In the seventh world, they thought the Bounds were sacred. I came out of the Boundary temple to see a whole line of temples stretching away into the distance, just like my cousin Marie’s wedding cake, one tall white wedding cake to every hilltop.

Anyway, I was going to say there were other signs on the other two sides of the Boundaries when I came to look. I picked up a good many that way. Then came one I’d never seen before. I’ve seen it quite a lot since. It means RANDOM and I’m usually glad to see it. That was how I got out of that wretched ring of worlds and met a few other Homeward Bounders at last.

III

I had got back to the cattle world by then. As soon as I arrived, I knew I was not going to be there long, and I would have been pleased, only by then I knew that the mining world came next.

“Oh please!” I prayed out loud, but not to Them. “Please not that blistering-oath mining world again! Anywhere else, but not that!”

The cattle country was bad enough. I never met the same people twice in it, of course. The earlier ones had moved off or died by the time I came round again. The ones I met were always agreeable, but they never did anything. It was the most boring place. I used to wonder if the Them playing it had gone to sleep on the job. Or maybe they were busy in a part of that world I never got to, and kept this bit just marking time. However it was, I was in for another session of dairy-farming, and I was almost glad it would only be a little one. Glad, that is, but for the mining horror that came next.

It was only three days before I felt the Bounds call. I was surprised. I hadn’t known it would be that short. By that time I had gone quite a long way down south with a moving tribe I fell in with. They were going down to the sea, and I wanted to go too. I had still never seen the sea then, believe it or not. I was really annoyed to feel the tugging, and the yearning in my throat, start so soon.

But I was an old hand by then. I thought I would bear it, stick it out for as long as possible, and put off the mining world for as long as I could. So I ground my teeth together and kept sitting on the horse they’d lent me and jogging away south.

And suddenly the dragging and the yearning took hold of me from a different direction, almost from the way we were going. I was so confused I fell off the horse. While I was sitting on the grass with my hands over my head, waiting for the rest of the tribe to get by before I dared get up—you get kicked in the head if you try crawling about under a crowd of horses—the next part of the call started: the “Hurry, hurry, you’ll be late!” It’s always sooner and stronger if you get it from a new direction. It’s always stronger from a RANDOM Boundary too. I don’t know why. This was so strong that I found I couldn’t wait any longer. I got up and started running.

They shouted after me of course. They’re scared of people going off on their own, even though nothing ever happens to them. But I took no notice and kept running, and they didn’t have a Mrs. Chief with them—theirs was a sleepy girl who never bothered about anything—so they didn’t follow me. I stopped running when I was over the nearest hill and walked. I knew by then that the “Hurry, hurry!” was only meant to get me going. It didn’t mean much.

It was just as well it didn’t mean much. It took me the rest of that day and all night to get there, and the funny colored sun was two hours up before I saw the Boundary. This was a new one. It was marked by a ring of stones.

I stared at it a little as I went down into the valley where it was. They were such big stones. I couldn’t imagine any hairy cattle herders having the energy to make it. Unless They had done it, of course. I stared again when I saw the new sign scrawled on the nearest huge stone, some way above my head.

“I wonder what that means,” I said. But I had been a long time on the way and the call was getting almost too strong to bear. I stopped wondering and went into the circle.

And—twitch—I was drowning in an ocean.

Yes, I saw the sea after all—from inside. At least, I was inside for what seemed about five minutes, until I came screaming and drowning and kicking up to the surface, and coughing out streams of fierce salt water—only to have all my coughing undone the next moment by a huge great wave, which came and hit me slap in the face, and sent me under again. I came up again pretty fast. I didn’t care that nothing could stop a Homeward Bounder. I didn’t believe it. I was drowning.

It isn’t true what they say about your life passing before you. You’re too busy. You’re at it full time, bashing at the water with your arms and screaming “Help!” to nothing and nobody. And too busy keeping afloat. I hadn’t the least idea how to swim. What I did was a sort of crazy jumping up and down, standing in the water, with miles more water down underneath me, bending and stretching like a mad frog, and it kept me up. It also turned me round in a circle. Every way was water, with sky at the end of it. Nothing in sight at all, except flaring sunlit water on one side and heaving gray water on the other.

That had me really panicked. I jumped and screamed like a madman. And here was a funny thing—somebody seemed to be answering. Next moment, a sort of black cliff came sliding past me, and someone definitely shouted. Something that looked like a frayed rope splashed down in the sea in front of me. I dived on it with both hands, which sent me under again, even though I caught the rope. I was hauled up like that, yelling and sousing and shivering, and went bumping up the side of that sudden black cliff.

It was like going up the side of a cheese-grater—all barnacles. I left quite a lot of skin on there, and a bit more being dragged over the top. I remember realizing it was a boat and then looking at who’d rescued me. And I think I passed out. Certainly I remember nothing else until I was lying on a mildewy bed, under a damp blanket,

and thinking, This can’t be true! I can’t have been pulled out of the sea by a bunch of monkeys! But that was what I seemed to have seen. I knew that, even with my eyes closed. I had seen skinny thin hairy arms and shaggy faces with bright monkey eyes, all jabbering at me. It must be true, I thought. I must be in a world run by monkeys now.

At that point, someone seized my head and tried to suffocate me by pouring hellfire into my mouth. I did a lot more coughing. Then I gently opened one watery eye and took a look at the monkey who was doing it to me.

This one was a man. That was some comfort, even though he was such a queer-looking fellow. He had the remains of quite a large square face. I could see that, though a lot of it was covered by an immense black beard. Above the beard, his cheeks were so hollow that it looked as if he were sucking them in, and his eyes had gone right back into his head somehow, so that his eyebrows turned corners on top of them. His hair was as bad as his beard, like a rook’s nest. The rest of him looked more normal, because he was covered up to the chin in a huge navy-blue coat with patches of mold on it. But it probably only looked normal. The hand he stretched out—with a bottle in it to choke me with hellfire again—was like a skeleton’s.

I jumped back from that bottle. “No thanks. I’m fine now.”

He bared his teeth at me. He was smiling. “Ah, ve can onderstand von anodder!” That is a rough idea of the way he spoke. Now, I’ve been all over the place, and changed my accent a good twenty times, but I always speak English like a native. He didn’t. But at least I seemed to be in a world where someone spoke it.

“Who are you?” I said.

He looked reproachful at that. I shouldn’t have asked straight out. “Ve ollways,” he said—I can’t do the way he spoke—“we always keep one sharp lookout coming through the Boundaries, in case any other Homeward Bounder in the water lies. Lucky for you, eh!”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

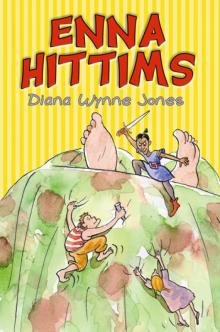

Reflections Enna Hittms

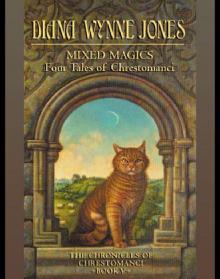

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci