- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

The Ogre Downstairs Page 3

The Ogre Downstairs Read online

Page 3

Johnny sighed, but he obediently trudged off to the bathroom for soap and water. He returned, still thoughtful, and remained so all the time he was rubbing the carpet with the Ogre’s face flannel. The stain came off fairly easily and dyed the flannel deep mauve.

“Couldn’t you have used yours or mine?” said Caspar.

“I did. Douglas made me use them on their room,” said Johnny. “Listen. Gwinny got an awful lot of that stuff on her, didn’t she? Suppose you use less, so you weren’t quite so light, wouldn’t you be like flying?”

“Hey!” said Caspar, sitting up in bed. Since he had had to change all his clothes, it had seemed the simplest place to be. “That’s an idea! What did you put in it?”

“I can’t remember,” said Johnny. “But I’m darned well going to find out.”

CHAPTER THREE

In the days that followed, Johnny experimented. He made black mixtures, green mixtures and red ones. He made little smells, big smells, and smells grandiose and appalling. These met with the smells coming from Malcolm’s efforts and mingled with them, until Sally said that their landing seemed like a plague spot to her. But whatever smell or colour Johnny made, he was no nearer finding the right mixture. He went on doggedly. He remembered that Gwinny had put pipe ash in the mixture, so he always made that one of the ingredients.

“Who is it keeps taking my pipes?” demanded the Ogre, and received no answer. And in spite of running this constant risk, Johnny’s efforts were not rewarded. Nevertheless, he persevered. It was his nature to be dogged, and Caspar and Gwinny were thankful for it; for, as Gwinny said, the idea of being really able to fly made it easier to bear the awfulness of everything else.

Each day seemed to bring fresh trials. First there was the trouble over the purple face flannel, and then the affair of the muddy sweater on the roof, mysteriously found wrapped round the chimney. The Ogre, as a matter of course, blamed Caspar, and when Caspar protested his innocence, he blamed Johnny. And twice Caspar forgot that the Ogre was at home and played Indigo Rubber – the third time, the noise came from Douglas, but Douglas said nothing and let Caspar take the blame.

Then the weather turned cold. The house had very old central heating, which seemed too weak to heat all four floors properly. The bathroom, and the bedroom shared by Sally and the Ogre, were warm enough, but upwards from there it grew steadily colder. Gwinny’s room got so cold that she took to sneaking down to her mother’s room and curling up on the big soft bed to read. Unfortunately, she left a toffee bar on the Ogre’s pillow one evening, and the boys were blamed again. It took all Gwinny’s courage to own up, and the Ogre was in no way impressed by her heroism. However, he did find her an old electric heater, which he installed in her room with instructions not to waste electricity.

“We don’t need to be pampered,” Malcolm said odiously. “You should see what it’s like at a boarding school before you complain here.”

“Quait,” said Caspar. “Full of frosty little snobs like you. Why don’t you go back there where you belong?”

“I wish I could,” Malcolm retorted, with real feeling. “Anything would be better than having to share this pigsty with you.”

Nearly a week passed. One afternoon, Caspar was as usual hurrying home in order not to have to walk back with Malcolm, when he discovered himself to be in a silly kind of mood. He knew he was going to have to act the goat somehow. He decided to do it in the Ogre’s study, if possible, because it was the warmest room in the house and also possessed a nice glossy parquet floor, ideal for sliding on. As soon as he got home, he hurried to the study and cautiously opened its door.

The Ogre was not there, but Johnny was. He was rather gloomily turning ash out of the Ogre’s pipes into a tin for further experiments.

“How’s it going?” Caspar asked, slinging his bag into the Ogre’s chair and sitting on the Ogre’s desk to take his shoes off.

Johnny jumped. The Ogre’s inkwell fell over, and Johnny watched the ink spreading with even deeper gloom. “He’ll know it’s me,” he said. “He always thinks it’s me anyway.”

“Unless he thinks it’s me,” said Caspar, casting his shoes to the floor. “Wipe it up, you fool. But is the Great Caspar daunted by the Ogre? Yes, he is rather. And the ink is running off the desk into his shoes.”

Johnny, knowing he would get no sense out of Caspar in this mood, picked up the Ogre’s blotting paper and put it in the pool of ink. The blotting paper at once became bright blue and sodden, but there seemed just as much ink as before.

Gwinny came in, hearing their voices. “There’s ink running off on to the floor,” she said.

“Tell me something I don’t know,” said Johnny, wondering how one small inkwell always contained such floods of ink.

“I’ll do the floor,” said Gwinny. “Can’t you help, Caspar?”

“No,” said Caspar, gliding smoothly in his socks across the floor. He did not see why he should be deprived of his pleasure because of Johnny’s clumsiness.

“Well, we think you’re mean,” said Gwinny, fetching a newspaper from the rack and laying it under the streams of ink.

“The Great Caspar,” said Caspar, “is extremely generous.”

“Take no notice,” said Johnny. “And pass me a newspaper.”

Caspar continued to slide. “The Great Caspar,” he said kindly, “will slide for your entertainment while you work, lady and gentleman. He has slid before all the crowned heads of Europe, and will now perform, solely for your benefit, the famous hexagonal turn. Not only has it taken him years to perfect but—”

“Oh shut up!” said Johnny, desperately wiping.

“—it is also very hazardous,” said Caspar. “Behold, the hazardous hexagon!” Upon this, Caspar spun himself round and attempted to jump while he did it. While he was in the air, he saw the Ogre in the doorway, lost his balance and ended sitting in a pool of ink. From this position, he looked up into the dour face of the Ogre. His own face was vivid red, and he hoped most earnestly that the Ogre had not heard his boastful fooling.

The Ogre had heard. “The Great Caspar,” the Ogre said, “appears to have some difficulty with the hexagonal turn. Get up! AND GET OUT!”

To complete Caspar’s humiliation, Malcolm appeared in the doorway, snorting with laughter. “What is a hexagonal turn?” he said.

The Ogre’s roar had fetched Sally too. “Oh just look at this mess!” she cried. “Those trousers are ruined, Caspar. Don’t any of you have the slightest consideration? Ink all over poor Jack’s study!”

It was the last straw, being blamed for falling in the ink. Caspar, with difficulty, climbed to his feet. “Poor Jack!” he said, with his voice shaking with rage, and fear at his own daring. “It’s always poor flipping Jack! What about poor us for a change?”

The hurt, harrowed look on Sally’s face deepened. The Ogre’s face became savage and he moved towards Caspar with haste and purpose. Caspar did not wait to discover what the purpose was. With all the speed his slippery socks would allow, he dodged the Ogre, dived between Malcolm and Sally and fled upstairs.

There he changed into jeans, muttering. His face was red, his eyes stung with misery and he could not stop himself making shamed, angry noises. “I wish I was dead!” he said, and surged towards the window, wondering whether he dared throw himself out. His progress scattered construction kits and hurled paper about. He knocked against a corner of the chemistry box. It shunted into its lid, which Johnny had left lying beside it, and a tube of some white chemical lying on the lid rolled across it and spilt a little white powder on Caspar’s sock as he passed.

Caspar found himself reaching the window in two graceful slow-motion bounds, rather like a ballet dancer’s, except that his socks barely met the floor as he passed. And when he was by the window, instead of stopping in the usual way, his feet again left the floor in a long, slow, drifting bounce. Hardly had he realised what was happening, than he was down again, quite in the usual way, with a heavy bump, on top of what f

elt like a drawing pin.

He was so excited that he hardly noticed it. He simply pulled off his sock, and the drawing pin with it, and waded back with one bare foot to the chemistry set. The little tube of chemical was trembling on the edge of the lid and white powder was filtering down from it on to the carpet. Caspar’s hands shook rather as he picked it up. He planted its stopper firmly in, and then turned it over to read the label. It read Vol. pulv., which left Caspar none the wiser. But the really annoying thing was that the little tube was barely half full. Either most of it had gone the night Gwinny took to the ceiling, or Johnny had unwittingly used it up since in other mixtures that destroyed its potency. Wondering just how potent the powder was, Caspar carefully put his bare foot on the place where the tube had spilt. When nothing happened, he trod harder and screwed his foot around.

He was rewarded with a delicious feeling of lightness. A moment later, his feet left the ground and he was hanging in the air about eighteen inches above the littered floor. He was not very light. He gave a scrambling sort of jump to see if he could go any higher, and all that happened was that he bounced sluggishly over towards the window. It was such a splendid feeling that he bounced himself again and went jogging slowly towards Johnny’s bed.

“Yippee!” he said, and began to laugh.

He invented a kind of dance then, by jumping with both feet together first to one side and then to the other. Bounce and… Bounce and… His head swung, his hair flew, and he brandished the tube in his hand. Bounce and… Bounce and… “Yippee!”

Johnny and Gwinny came soberly and mournfully into the room while he was doing it. For a moment they could not believe their eyes. Then Johnny hastily slammed the door shut.

“I’ve found it!” said Caspar, bouncing away and waving the tube at them. “I’ve found it! It’s called Vol. pulv. and it works by itself. Yippee!” He suddenly felt himself becoming heavy again and was just in time to bounce himself over to his bed before the powder stopped working and he came down with a flop that made the bedsprings jangle. He sat there laughing and waving the tube at the others.

“How marvellous!” said Gwinny. “You are clever, Caspar.”

Johnny came slowly over to the bed. He took the tube and looked at it. “I was going to try this one today,” he said.

Caspar looked up at his gloomy face and understood that Johnny, not unreasonably, was feeling how unfair it was that Caspar should discover the secret, when Johnny had worked so hard over it and had just been in dire trouble about the ink as well. “You still need to do a lot of work on it,” Caspar said tactfully. “I used it dry, and it ought to be mixed with water. You’ll have to work out the right proportions.”

Johnny’s face brightened. “Yes,” he said. “And experiment to find out how much you need, not to go soaring right out of the atmosphere. I’ll have to do tests on myself, bit by bit.”

“That’s right,” agreed Caspar. “But for goodness sake don’t use too much while you do it. The tube’s less than half full already.”

“I’ve got eyes,” Johnny said crossly. Then, feeling he was being rather ungracious, he added, “I’m the Great Scientist. I think of everything.”

He tried to make good his boast by fencing off a corner of the room, so that no accidents should happen while the experiments were in progress. For the rest of the evening he sat in this pen, carefully putting the powder, grain by grain, into a test tube of water, and then bathing his big toe with the result.

“What’s the matter with Johnny?” their mother wanted to know, when she came in around bedtime.

Johnny, by this time, was bobbing an inch or so from the floor. He took hold of a chair that was part of his fence to hold himself down, and pretended not to have heard.

“I knocked over one of his experiments this afternoon,” Caspar explained anxiously, “and he doesn’t want anybody to do it again. Be careful of him. He’s very angry.”

Sally gave Johnny a puzzled look. “All right, darling. I won’t interfere. It was you I wanted to talk to anyway, Caspar.”

“About what I said about Jack? I’m sorry,” Caspar said hurriedly, dreading a scene. Scenes with his mother were always painful, not because she scolded, but because she believed in absolute honesty.

Sure enough, she said, “That’s not quite the point, darling. I could see you were hurt and miserable, and it upset me. Can’t you bring yourself to like Jack a little better? He really is very nice, you know.”

“Why should I? He doesn’t like us,” Caspar retorted with equal honesty.

“He tries,” Sally said earnestly. “I can think of at least a hundred occasions when he’s been very forebearing indeed.”

“There are about a thousand when he hasn’t,” Caspar said bitterly.

“That’s partly because you’ve been so awful,” Sally said frankly. “Truly, I’m ashamed of you most of the time – all of you, but particularly you as the eldest.”

Caspar’s face was red and he wanted to mutter again. He looked over at Johnny. Johnny looked sulkily at his big toe and gave it a slight waggle. He was hating the scene as much as Caspar, and he was also mortally afraid that he was going to rise from his pen any minute and float about.

Caspar did his best to send Sally away. “I’m sorry,” he said, sounding so sincere and nice that he made himself feel ill. “I will try.” He was quite unable to keep up this level of piety. He found himself adding, “I do try, only he keeps blaming me so.”

“You must remember,” said Sally, “that he isn’t really used to children. Malcolm and Douglas have been away at school most of the time, and he simply had no idea what it could be like.”

“He’s finding out, isn’t he?” said Caspar.

Sally laughed. “You can say that again! All right. Good night, darlings. And do try a bit harder in future.”

She went out and shut the door. Johnny gave a sigh of relief, let go of the chair and bobbed clear of the floor again.

Before he went to bed, he had risen to three feet. Caspar was rather glad to find that there was no horrible smell this time, as the mixture in the test tube grew stronger. It must have been due to all the other things Johnny had put in. They were discussing it when Malcolm, in his usual manner, knocked and came in despite being told to go away. Johnny was only just in time to pull himself over to the cupboard and pretend to be sitting on top of it.

“My father says you’re to put your light out,” Malcolm said. His eyes wandered critically to Johnny. “What are you sitting up there with one shoe off for?”

“We’ve both got one shoe off,” said Caspar, stretching out his bare foot and wriggling the toes at Malcolm’s face. “It’s the badge of our secret society. Now go away.”

“You don’t think I came in here for pleasure, do you?” Malcolm said, and went away.

Johnny looked anxiously at Caspar. “Do you think he suspected anything?”

“He’s far too flipping dim for that,” said Caspar. “But you’d better be careful. If he did find out, he’d tell the Ogre like a shot.”

“I think I’ll stop now,” said Johnny. “For tonight.” So Caspar washed his big toe for him, and Johnny climbed off the cupboard and went to bed.

The next day, Johnny skipped games and pelted home from school to continue his experiments. When Caspar came in, he found Johnny, again with one shoe off, triumphantly floating just below the ceiling.

“Look at this!” he said. “I could go higher if I put more on, only all the powder’s in the water now and I don’t want to waste it. Can you take the test tube and prop it carefully on that stand down there?”

Caspar stood on the cupboard and took the test tube from Johnny’s reaching hand. Then he climbed down and propped it upright in Johnny’s pen, while Johnny looked on tensely from the ceiling.

“What are you going to do now?” Caspar asked. “Come down?”

“I think I ought to practise a bit,” said Johnny. “You hold the door in case Malcolm comes in.”

&

nbsp; Caspar stood against the door and watched a little wistfully while Johnny pushed off from the ceiling and swooped this way and that across the room, as Gwinny had done. It looked enormous fun. Johnny was laughing. And now that he knew what a splendid feeling it was to be nearly as light as air, Caspar could hardly wait to get up there and swoop about himself.

“Hadn’t I better shut the window?” he called up at Johnny’s whisking feet.

“It’s all right,” Johnny said happily. “It’s quite easy to control where you go. Like swimming, only not such hard work.”

Caspar watched him doing slow, swooping breaststroke through the air, and yearned to see what a fast overarm would do. “When shall we all try?”

Johnny turned over and trod water, or rather air. “What about going out tonight, after dark, for a fly round town?”

Caspar was about to say that this was the best idea Johnny had had in his life, when there was a thump on the door behind him. He flung himself against it, with his feet braced. “Go away. We’re busy.”

“Buzz off!” Johnny shouted down from the ceiling.

The doorknob began turning. Caspar grabbed it and held it hard. In spite of this, the knob continued to turn and the door moved slightly. Caspar had not thought Malcolm was so strong. “Go away!” he said.

“I only want to borrow Indigo Rubber,” said a much deeper voice than Malcolm’s. “What’s so special that I can’t come in?”

Caspar looked up helplessly at Johnny’s alarmed face. “I thought you didn’t like Indigo Rubber,” he shouted through the door.

“I’ve come round to them,” Douglas called back. “And I’ve got some friends coming tonight who want to hear it.”

“You can’t have it,” called Caspar.

“But I promised them,” said Douglas. “Be a sport.”

“You’d no business to promise them my records!” Caspar said, with real indignation. “You can’t have them. Go away.”

“I knew you’d go and be mean about it,” said Douglas. “It’s typical. I only want to borrow their second LP for an hour this evening. I won’t hurt it, and you can come and listen, if you like. Father’s said we can have it in the dining room.”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

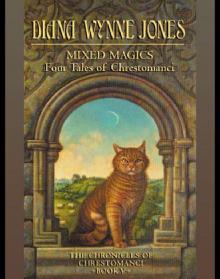

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

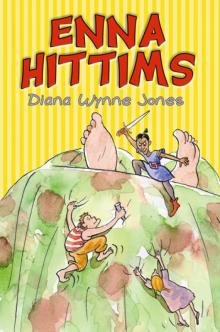

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci