- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

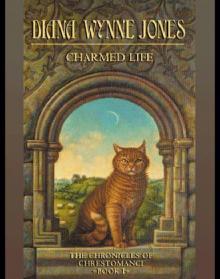

Charmed Life (UK) Page 3

Charmed Life (UK) Read online

Page 3

“Yes. Mr Nostrum told me there was a cab here,” gasped Gwendolen.

She was followed by Mrs Sharp, nearly as breathless. The two of them took over the conversation, and Cat was thankful for it. Chrestomanci at last consented to be taken to the parlour, where Mrs Sharp deferentially offered him a cup of tea and a plate of her weakly waving gingerbread men. Chrestomanci, Cat was interested to see, did not seem to have the heart to eat them either. He drank a cup of tea – austerely, without milk or sugar – and asked questions about how Gwendolen and Cat came to be living with Mrs Sharp. Mrs Sharp tried to give the impression that she looked after them for nothing, out of the goodness of her heart. She hoped Chrestomanci might be induced to pay her for their keep, as well as the Town Council.

But Gwendolen had decided to be radiantly honest. “The town pays,” she said, “because everyone’s so sorry about the accident.” Cat was glad she had explained, even though he suspected that Gwendolen might already be casting Mrs Sharp off like an old coat.

“Then I must go and speak to the Mayor,” Chrestomanci said, and he stood up, dusting his splendid hat on his elegant sleeve. Mrs Sharp sighed and sagged. She knew what Gwendolen was doing, too. “Don’t be anxious, Mrs Sharp,” said Chrestomanci. “No one wishes you to be out of pocket.” Then he shook hands with Gwendolen and Cat and said, “I should have come to see you before, of course. Forgive me. Your father was so infernally rude to me, you see. I’ll see you again, I hope.” Then he went away in the cab, leaving Mrs Sharp very sour, Gwendolen jubilant, and Cat nervous.

“Why are you so happy?” Cat asked Gwendolen.

“Because he was touched at our orphaned state,” said Gwendolen. “He’s going to adopt us. My fortune is made!”

“Don’t talk such nonsense!” snapped Mrs Sharp. “Your fortune is the same as it ever was. He may have come here in all his finery, but he said nothing and he promised nothing.”

Gwendolen smiled confidently. “You didn’t see the heart-wringing letter I wrote.”

“Maybe. But he’s not got a heart to wring,” Mrs Sharp retorted. Cat rather agreed with Mrs Sharp – particularly as he had an uneasy feeling that, before Gwendolen and Mrs Sharp arrived, he had somehow managed to offend Chrestomanci as badly as his father once did. He hoped Gwendolen would not realise. He knew she would be furious with him.

But, to his astonishment, Gwendolen proved to be right. The Mayor called that afternoon and told them that Chrestomanci had arranged for Cat and Gwendolen to come and live with him as part of his own family. “And I see I needn’t tell you what lucky little people you are,” he said, as Gwendolen uttered a shriek of joy and hugged the dour Mrs Sharp.

Cat felt more nervous than ever. He tugged the Mayor’s sleeve. “If you please, sir, I don’t understand who Chrestomanci is.”

The Mayor patted him kindly on the head. “A very eminent gentleman,” he said. “You’ll be hobnobbing with all the crowned heads of Europe before long, my boy. What do you think of that, eh?”

Cat did not know what to think. This had told him precisely nothing, and made him more nervous than ever. He supposed Gwendolen must have written a very touching letter indeed.

So the second great change came about in Cat’s life, and very dismal he feared it would be. All that next week, while they were hurrying about being bought new clothes by Councillors’ wives, and while Gwendolen grew more and more excited and triumphant, Cat found he was missing Mrs Sharp, and everyone else, even Miss Larkins, as if he had already left them. When the time came for them to get on the train, the town gave them a splendid send-off, with flags and a brass band. It upset Cat. He sat tensely on the edge of his seat, fearing he was in for a time of strangeness and maybe even misery.

Gwendolen, however, spread out her smart new dress and arranged her nice new hat becomingly, and sank elegantly back in her seat. “I did it!” she said joyously. “Cat, isn’t it marvellous?”

“No,” Cat said miserably. “I’m homesick already. What have you done? Why do you keep being so happy?”

“You wouldn’t understand,” said Gwendolen. “But I’ll tell you part of it. I’ve got out of dead-and-alive Wolvercote at last – stupid Councillors and piffling necromancers! And Chrestomanci was bowled over by me. You saw that, didn’t you?”

“I didn’t notice specially,” said Cat. “I mean, I saw you were being nice to him—”

“Oh, shut up, or I’ll give you worse than cramps!” said Gwendolen. And, as the train at last chuffed and began to draw out of the station, Gwendolen waved her gloved hand to the brass band, up and down, just like Royalty. Cat realised she was setting out to rule the world.

CHAPTER THREE

The train journey lasted about an hour, before the train puffed into Bowbridge, where they were to get out.

“It’s frightfully small,” Gwendolen said critically.

“Bowbridge!” shouted a porter, running along the platform. “Bowbridge. The young Chants alight here, please.”

“Young Chants!” Gwendolen said disdainfully. “Can’t they treat me with more respect?” All the same, the attention pleased her. Cat could see that, as she drew on her ladylike gloves, she was shaking with excitement. He cowered behind her as they got out and watched their trunks being tossed out on to the windy platform. Gwendolen marched up to the shouting porter. “We are the young Chants,” she told him magnificently.

It fell a little flat. The porter simply beckoned and scurried away to the entrance lobby, which was windier even than the platform. Gwendolen had to hold her hat on. Here, a young man strode towards them in a billow of flapping coat.

“We are the young Chants,” Gwendolen told him.

“Gwendolen and Eric? Pleased to meet you,” said the young man. “I’m Michael Saunders. I’ll be tutoring you with the other children.”

“Other children?” Gwendolen asked him haughtily. But Mr Saunders was evidently one of those people who are not good at standing still. He had already darted off to see about their trunks. Gwendolen was a trifle annoyed. But when Mr Saunders came back and led them outside into the station yard, they found a motor car waiting – long, black and sleek. Gwendolen forgot her annoyance. She felt this was entirely fitting.

Cat wished it had been a carriage. The car jerked and thrummed and smelt of petrol. He felt sick almost at once. He felt sicker still when they left Bowbridge and thrummed along a winding country road. The only advantage he could see was that the car went very quickly. After only ten minutes, Mr Saunders said, “Look – there’s Chrestomanci Castle now. You get the best view from here.”

Cat turned his sick face and Gwendolen her fresh one the way he pointed. The Castle was grey and turreted, on the opposite hill. As the road turned, they saw it had a new part, with a spread of big windows, and a flag flying above. They could see grand trees – dark, layered cedars and big elms – and glimpse lawns and flowers.

“It looks marvellous,” Cat said sickly, rather surprised that Gwendolen had said nothing. He hoped the road did not wind too much in getting to the Castle.

It did not. The car flashed round a village green and between big gates. Then there was a long tree-lined avenue, with the great door of the old part of the Castle at the end of it. The car scrunched round on the gravel sweep in front of it. Gwendolen leant forward eagerly, ready to be the first one out. It was clear there would be a butler, and perhaps footmen too. She could hardly wait to make her grand entry.

But the car went on, past the grey, knobbly walls of the old Castle, and stopped at an obscure door where the new part began. It was almost a secretive door. There was a mass of rhododendron trees hiding it from both parts of the Castle.

“I’m taking you in this way,” Mr Saunders explained cheerfully, “because it’s the door you’ll be using mostly, and I thought it would help you find your way about if you start as you mean to go on.”

Cat did not mind. He thought the door looked more homely. But Gwendolen, cheated of her grand entry, threw Mr Saunde

rs a seething look and wondered whether to say a most unpleasant spell at him. She decided against it. She was still wanting to give a good impression. They got out of the car and followed Mr Saunders – whose coat had a way of billowing even when there was no wind – into a square polished passageway indoors.

A most imposing lady was waiting there to meet them. She was wearing a tight purple dress, and her hair was in a very tall jet-black pile. Cat thought she must be Mrs Chrestomanci.

“This is Miss Bessemer, the housekeeper,” said Mr Saunders. “Eric and Gwendolen, Miss Bessemer. Eric’s a bit car-sick, I’m afraid.”

Cat had not realised his trouble was so obvious. He was embarrassed. Gwendolen, who was very annoyed to be met by a mere housekeeper, held her hand out coldly to Miss Bessemer.

Miss Bessemer shook hands like an Empress. Cat was just thinking she was the most awe-inspiring lady he had ever met, when she turned to him with a very kind smile. “Poor Eric,” she said. “Riding in a car bothers me ever so, too. You’ll be all right now you’re out of the thing – but if you’re not, I’ll give you something for it. Come and get washed, and have a look-see at your rooms.”

They followed the narrow purple triangle of her dress up some stairs, along corridors, and up more stairs. Cat had never seen anywhere so luxurious. There was carpet the whole way – a soft green carpet, like grass in the dewy morning – and the floor at the sides was polished so that it reflected the carpet and the clean white walls and the pictures hung on the walls. Everywhere was very quiet. They heard nothing the whole way, except their own feet and Miss Bessemer’s purple rustle.

Miss Bessemer opened a door on to a blaze of afternoon sun. “This is your room, Gwendolen. Your bathroom opens off it.”

“Thank you,” said Gwendolen, and she sailed magnificently in to take possession of it. Cat peeped past Miss Bessemer and saw the room was very big, with a rich, soft Turkey carpet covering most of the floor.

Miss Bessemer said, “The Family dines early when there are no visitors, so that they can eat with the children. But I expect you’d like some tea all the same. Whose room shall I have it sent to?”

“Mine, please,” said Gwendolen at once.

There was a short pause before Miss Bessemer said, “Well, that’s settled then, isn’t it? Your room is up here, Eric.”

The way was up a twisting staircase. Cat was pleased. It looked as if his room was going to be part of the old Castle. And he was right. When Miss Bessemer opened the door, the room beyond was round, and the three windows showed that the wall was nearly three feet thick. Cat could not resist racing across the glowing carpet to scramble on one of the deep window-seats and look out. He found he could see across the flat tops of the cedars to a great lawn like a sheet of green velvet, with flower gardens going down the hillside in steps beyond it. Then he looked round the room itself. The curved walls were whitewashed, and so was the thick fireplace. The bed had a patchwork quilt on it. There was a table, a chest-of-drawers and a bookcase with interesting-looking books in it.

“Oh, I like this!” he said to Miss Bessemer.

“I’m afraid your bathroom is down the passage,” said Miss Bessemer, as if this was a drawback. But, as Cat had never had a private bathroom before, he did not mind in the least.

As soon as Miss Bessemer had gone, he hastened along to have a look at it. To his awe, there were three sizes of red towel and a sponge as big as a melon. The bath had feet like a lion’s. One corner of the room was tiled, with red rubber curtains, for a shower. Cat could not resist experimenting. The bathroom was rather wet by the time he had finished. He went back to his room, a little damp himself. His trunk and box were there by this time, and a maid with red hair was unpacking them. She told Cat her name was Mary, and wanted to know if she was putting things in the right places. She was perfectly pleasant, but Cat was very shy of her. The red hair reminded him of Miss Larkins, and he could not think what to say to her.

“Er – may I go down and have some tea?” he stammered.

“Please yourself,” she said – rather coldly, Cat thought. He ran downstairs again, feeling he might have got off on the wrong foot with her.

Gwendolen’s trunk was standing in the middle of her room. Gwendolen herself was sitting in a very queenly way at a round table by the window, with a big pewter teapot in front of her, a plate of brown bread and butter, and a plate of biscuits.

“I told the girl I’d unpack for myself,” she said. “I’ve got secrets in my trunk and my box. And I asked her to bring tea at once because I’m starving. And just look at it! Did you ever see anything so dull? Not even jam!”

“Perhaps the biscuits are nice,” Cat said hopefully. But they were not, or not particularly.

“We shall starve, in the midst of luxury!” sighed Gwendolen.

Her room was certainly luxurious. The wallpaper seemed to be made of blue velvet. The top and bottom of the bed was upholstered like a chair, in blue velvet with buttons in it, and the blue velvet bedspread matched it exactly. The chairs were painted gold. There was a dressing-table fit for a princess, with little golden drawers, gold-backed brushes, and a long oval mirror surrounded by a gilded wreath. Gwendolen admitted that she liked the dressing-table, though she was not so sure about the wardrobe, which had painted garlands and maypole-dancers on it.

“It’s to hang clothes in, not to look at,” she said. “It distracts me. But the bathroom is lovely.”

The bathroom was tiled with blue and white tiles, and the bath was sunk down into the tiled floor. Over it, draped like a baby’s cradle, were blue curtains for when you wanted a shower. The towels matched the tiles. Cat preferred his own bathroom, but that may have been because he had to spend rather a long time in Gwendolen’s. Gwendolen locked him in it while she unpacked. Through the hiss of the shower – Gwendolen had only herself to blame that she found her bathroom thoroughly soaked afterwards – Cat heard her voice raised in annoyance at someone who had come in to take the dull tea away and caught her with her trunk open. When Gwendolen finally unlocked the bathroom door, she was still angry.

“I don’t think the servants here are very civil,” she said. “If that girl says one thing more, she’ll find herself with a boil on her nose – even if her name is Euphemia! Though,” Gwendolen added charitably, “I’m inclined to think being called Euphemia is punishment enough for anyone. You have to go and get your new suit on, Cat. She says dinner’s in half an hour and we have to change for it. Did you ever hear anything so formal and unnatural!”

“I thought you were looking forward to that kind of thing,” said Cat, who most certainly was not.

“You can be grand and natural,” Gwendolen retorted. But the thought of the coming grandeur soothed her all the same. “I shall wear my blue dress with the lace collar,” she said. “And I do think being called Euphemia is a heavy enough burden for anyone to bear, however rude they are.”

As Cat went up his winding stair, the Castle filled with a mysterious booming. It was the first noise he had heard. It alarmed him. He learnt later that it was the dressing-gong, to warn the Family that they had half an hour to change in. Cat, of course, did not take nearly that time to put his suit on. So he had yet another shower. He felt damp and weak and almost washed out of existence by the time the maid who was so unfortunate in being called Euphemia came to take him and Gwendolen downstairs to the drawing room where the Family was waiting.

Gwendolen, in her pretty blue dress, sailed in confidently. Cat crept behind. The room seemed full of people. Cat had no idea how all of them came to be part of the Family. There was an old lady in lace mittens, and a small man with large eyebrows and a loud voice who was talking about stocks and shares; Mr Saunders, whose wrists and ankles were too long for his shiny black suit; and at least two younger ladies; and at least two younger men. Cat saw Chrestomanci, quite splendid in very dark red velvet; and Chrestomanci saw Cat and Gwendolen and looked at them with a vague, perplexed smile, which made Cat quite sure that Chr

estomanci had forgotten who they were.

“Oh,” said Chrestomanci. “Er. This is my wife.”

They were ushered in front of a plump lady with a mild face. She had a gorgeous lace dress on – Gwendolen’s eyes swept up and down it with considerable awe – but otherwise she was one of the most ordinary ladies they had ever seen. She gave them a friendly smile. “Eric and Gwendolen, isn’t it? You must call me Millie, my dears.” This was a relief, because neither of them had any idea what they should have called her. “And now you must meet my Julia and my Roger,” she said.

Two plump children came and stood beside her. They were both rather pale and had a tendency to breathe heavily. The girl wore a lace dress like her mother’s, and the boy had on a blue velvet suit, but no clothes could disguise the fact that they were even more ordinary-looking than their mother. They looked politely at Gwendolen and at Cat, and all four said, “How do you do?” Then there seemed nothing else to say.

Luckily, they had not stood there long before a butler came and opened the double doors at the end of the room, and told them that dinner was served. Gwendolen looked at this butler in great indignation. “Why didn’t he open the door to us?” she whispered to Cat, as they all went in a ragged sort of procession to the dining room. “Why were we fobbed off with the housekeeper?”

Cat did not answer. He was too busy clinging to Gwendolen. They were being arranged round a long polished table, and if anyone had tried to put Cat in a chair that was not next to Gwendolen’s he thought he would have fainted from terror. Luckily, no one tried. Even so, the meal was terrifying enough. Footmen kept pushing delicious food in silver plates over Cat’s left shoulder. Each time that happened, it took Cat by surprise, and he jumped and jogged the plate. He was supposed to help himself off the silver plate, and he never knew how much he was allowed to take. But the worst difficulty was that he was left-handed. The spoon and fork that he was supposed to lift the food with from the footman’s plate to his own were always the wrong way round. He tried changing them over, and dropped a spoon. He tried leaving them as they were, and spilt gravy. The footman always said, “Not to worry, sir,” and made him feel worse than ever.

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci