- Home

- Diana Wynne Jones

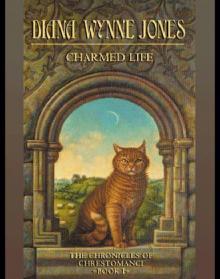

Charmed Life (UK) Page 7

Charmed Life (UK) Read online

Page 7

“Well, I had at least two other things in mind besides witchcraft.” Mr Saunders said. “But what makes you think you’d be no good?”

“Because I can’t do it,” Cat explained. “Spells just don’t work for me.”

“Are you sure you went about them in the right way?” Mr Saunders asked. He wandered up to the mummified dragon – or whatever – and gave it an absent-minded flick. To Cat’s disgust, the thing twitched all over. Filmy wings jerked and spread on its back. Then it went lifeless again. The sight sent Cat backing towards the door. He was almost as alarmed as he was the time Miss Larkins suddenly spoke with a man’s voice. And, come to think of it, the voice had been not so unlike Mr Saunders’s.

“I went about it every way I could think,” Cat said, backing. “And I couldn’t even turn buttons into gold. And that was simple.”

Mr Saunders laughed. “Perhaps you weren’t greedy enough. All right. Cut along, if you want to go.”

Cat fled, in great relief. As he ran through the strange corridors, he thought he ought to let Gwendolen know that Chrestomanci had, after all, been interested in her apparition, and even angry. But Gwendolen had locked her door and would not answer when he called to her.

He tried again next morning. But, before he had a chance to speak to Gwendolen, Euphemia came in, carrying a letter. As Gwendolen snatched it eagerly from Euphemia, Cat recognised Mr Nostrum’s jagged writing on the envelope.

The next moment, Gwendolen was raging again. “Who did this? When did this come?” The envelope had been neatly cut open along the top.

“This morning, by the postmark,” said Euphemia. “And don’t look at me like that. Miss Bessemer gave it to me open.”

“How dare she!” said Gwendolen. “How dare she read my letters! I’m going straight to Chrestomanci about this!”

“You’ll regret it if you do,” said Euphemia, as Gwendolen pushed past her to the door.

Gwendolen whirled round on her. “Oh, shut up, you stupid frog-faced girl!” Cat thought that was a little unfair. Euphemia, though she did have rather goggling eyes, was actually quite pretty. “Come on, Cat!” Gwendolen shouted at him, and she ran away along the corridor with her letter. Cat panted behind her and, once again, did not catch up with her till they were beside the marble staircase. “Chrestomanci!” bawled Gwendolen, thin and small and unechoing.

Chrestomanci was coming up the marble staircase in a wide, flowing dressing-gown that was partly orange and partly bright pink. He looked like the Emperor of Peru. By the suave, vague look on his face, he had not noticed Gwendolen and Cat.

Gwendolen shouted down at him. “Here, you! Come here at once!” Chrestomanci’s face turned upwards and his eyebrows went up. “Someone’s been opening my letters,” said Gwendolen. “And I don’t care who it is, but I’m not having it! Do you hear?”

Cat gasped at the way she spoke. Chrestomanci seemed perplexed. “How are you not having it?” he said.

“I won’t put up with it!” Gwendolen shouted at him. “In future, my letters are going to come to me closed!”

“You mean you want me to steam them open and stick them down afterwards?” Chrestomanci asked doubtfully. “It’s more trouble, but I’ll do that if it makes you happier.”

Gwendolen stared at him. “You mean you did it? You read a letter addressed to me?”

Chrestomanci nodded blandly. “Naturally. If someone like Henry Nostrum writes letters to you, I have to make sure he’s not writing anything unsuitable. He’s a very seedy person.”

“He was my teacher!” Gwendolen said furiously. “You’ve no right to!”

“It’s a pity,” said Chrestomanci, “that you were taught by a hedge-wizard. You’ll have to unlearn such a lot. And it’s a pity too that I’ve no right to open your letters. I hope you don’t get many, or my conscience will give me no peace.”

“You intend to go on?” Gwendolen said. “Then watch out. I warn you!”

“That is very considerate of you,” said Chrestomanci. “I like to be warned.” He came up the rest of the marble stairs and went past Gwendolen and Cat. The pink and orange dressing-gown swirled, revealing a bright scarlet lining. Cat blinked.

Gwendolen stared vengefully as the dazzling dressing-gown flowed away along the gallery. “Oh no, don’t notice me, will you!” she said. “Make jokes. You wait! Cat, I’m so furious!”

“You were awfully rude,” said Cat.

“He deserved it,” said Gwendolen, and began to hurry back towards the playroom. “Opening poor Mr Nostrum’s letter! It isn’t that I mind him reading it. We arranged a code, so horrid Chrestomanci will never know what it’s really saying, but there is the signature. But it’s the insult. The indignity. I’m at their mercy in this Castle. I’m all on my own in distress and I can’t even stop them reading my letters. But I’ll show them. You wait!”

Cat knew better than to say anything. Gwendolen slammed into the playroom, flounced down at the table, and began at last to read her letter.

“I told you so,” said Euphemia, while Mary was working the lift.

Gwendolen shot her a look. “You wait, too,” she said, and went on reading. After a bit, she looked in the envelope again. “There’s one for you too,” she said to Cat, and tossed him a sheet of paper. “Mind you reply to it.”

Cat took it, wondering nervously why Mr Nostrum should write to him. But it was from Mrs Sharp. She wrote:

Me dear Cat,

Ow are you doin then me love? I fine meself lonesum an missin you both particular you the place seems so quiete. Thourght I was lookin forwards to a bit peace but missin yer voice an wishin you was comin in bringin appels. One thing happen an that was a gennelman come an give five poun for the ole cat that was yer fidel so I feel flush an had idear of packin you up a parsel of jinjerbredmen and mebbe bringin them to you one of these days but Mr Nostrum sez not to. Spect your in the lap of luckshury anyhows. Love to Gwendolen. Wish you was back here Cat and the money means nothin.

Your loving,

Ellen Sharp

Cat read this with a warm, smiling, tearful feeling. He found he was missing Mrs Sharp as much as she evidently missed him. He was so homesick he could not eat his bread, and the cocoa seemed to choke him. He did not hear one word in five that Mr Saunders said.

“Is something the matter with you, Eric?” Mr Saunders demanded.

As Cat dragged his mind back from Coven Street, the window blacked out. The room was suddenly pitch dark. Julia squeaked. Mr Saunders groped his way to the switch and turned the light on. As he did so, the window became transparent again, revealing Roger grinning, Julia startled, Gwendolen sitting demurely, and Mr Saunders with his hand on the switch looking irritably at her.

“I suppose the cause of this is outside the Castle grounds, is it?” he said.

“Outside the lodge gates,” Gwendolen said smugly. “I put it there this morning.” By this, Cat knew her campaign against Chrestomanci had been launched.

The window blacked out again.

“How often are we to expect this?” Mr Saunders said in the dark.

“Twice every half hour,” said Gwendolen.

“Thank you,” Mr Saunders said nastily, and he left the light on. “Now we can see, Gwendolen, write out one hundred times, I must keep the spirit of the law and not the letter and, Roger, take that grin off your face.”

All that day, all the windows in the Castle blacked out regularly twice every half hour. But if Gwendolen had hoped to make Chrestomanci angry, she did not succeed. Nothing happened, except that everyone kept the lights on all the time. It was rather a nuisance, but no one seemed to mind.

Before lunch, Cat went outside on to the lawn to see what the blackouts looked like from the other side. It was rather as if two black shutters were flicking regularly across the rows of windows. They started at the top right-hand corner, and flicked steadily across, along the next row from left to right and then from right to left along the next, and so on, until they reached the bo

ttom. Then they started at the top again. Cat had watched about half a complete performance, when he found Roger beside him, watching critically with his pudgy hands in his pockets.

“Your sister must have a very tidy mind,” Roger said.

“I think all witches have,” said Cat. Then he was embarrassed. Of course he was talking to one – or at least to a warlock in the making.

“I don’t seem to have,” Roger remarked, not in the least worried. “Nor has Julia. And I don’t think Michael has, really. Would you like to come and play in our tree-house after lessons?”

Cat was very flattered. He was so pleased that he forgot how homesick he was. He spent a very happy evening down in the wood, helping to rebuild the roof of the tree-house. He came back to the Castle when the dressing-gong went, and found that the window-spell was fading. When the windows darkened, it only produced a sort of grey twilight indoors. By the following morning, it was gone, and Chrestomanci had not said a word.

Gwendolen returned to the attack the next morning. She caught the baker’s boy as he cycled through the lodge gates with the square front container of his bicycle piled high with loaves for the Castle. The baker’s boy arrived at the kitchen looking a little dazed and saying his head felt swimmy. As a consequence, the children had to have scones for breakfast. It seemed that when the bread was cut, the most interesting things happened.

“You’re giving us all a good laugh,” Mary said, as she brought the scones from the lift. “I’ll say that for your naughtiness, Gwendolen. Roberts thought he’d gone mad when he found he was cutting away at an old boot. So Cook cuts another, and next moment she and Nancy are trying to climb on the same chair because of all those white mice. But it was Mr Frazier’s face that made me laugh most, when he says ‘Let me’ and finds himself chipping at a stone. Then the—”

“Don’t encourage her. You know what she’s like,” said Euphemia.

“Be careful I don’t start on you,” Gwendolen said sourly.

Roger found out privately from Mary what had happened to the other loaves. One had become a white rabbit, one had been an ostrich egg – which had burst tremendously all over the bootboy – and another a vast white onion. After that, Gwendolen’s invention had run out and she had turned the rest into cheese. “Old bad cheese, though,” Roger said, giving honour where honour was due.

It was not known whether Chrestomanci also gave honour where it was due, because, once again, he said not a word to anyone.

The next day was Saturday. Gwendolen caught the farmer delivering the churn of milk the Castle used daily. The breakfast cocoa tasted horrible.

“I’m beginning to get annoyed,” Julia said tartly. “Daddy may take no notice, but he drinks tea with lemon.” She stared meaningly at Gwendolen. Gwendolen stared back, and there was that invisible feeling of clashing Cat had noticed when Gwendolen had wanted her mother’s earrings from Mrs Sharp. This time, however, Gwendolen did not have things all her own way. She lowered her eyes and looked peevish.

“I’m getting sick of getting up early, anyway,” she said crossly.

This, from Gwendolen, simply meant she would do something later in the day in future. But Julia thought she had beaten Gwendolen, and this was a mistake.

They had lessons on Saturday morning, which annoyed Gwendolen very much. “It’s monstrous,” she said to Mr Saunders. “Why do we have to be tormented like this?”

“It’s the price I have to pay for my holiday on Wednesday,” Mr Saunders told her. “And, speaking of tormenting, I prefer you to bewitch something other than the milk.”

“I’ll remember that,” Gwendolen said sweetly.

CHAPTER SEVEN

It rained on Saturday afternoon. Gwendolen shut herself into her room, and once again Cat did not know what to do. He wrote to Mrs Sharp on the back of his postcard of the Castle, but that only took ten minutes, and it was too wet to go out and post it. Cat was hanging about at the foot of his stairs, wondering what to do now, when Roger came out of the playroom and saw him.

“Oh good,” said Roger. “Julia won’t play soldiers. Will you?”

“But I can’t – not like you do,” Cat said.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Roger. “Honestly.”

But it did. No matter how cunningly Cat deployed his lifeless tin army, as soon as Roger’s soldiers began to march, Cat’s men fell over like ninepins. They fell in batches and droves and in battalions. Cat moved them furiously this way and that, grabbing them by handfuls and scooping them with the lid of the box, but he was always on the retreat. In five minutes, he was reduced to three soldiers hidden behind a cushion.

“This is no good,” said Roger.

“No, it isn’t,” Cat agreed mournfully.

“Julia,” said Roger.

“What?” said Julia. She was curled in the shabbiest armchair, managing to suck a lollipop, to read a book called In the Hands of the Lamas, and to knit, all at the same time. Her knitting, hardly surprisingly, looked like a vest for a giraffe which had been dipped in six shades of grey dye.

“Can you make Cat’s soldiers move for him?” said Roger.

“I’m reading,” said Julia, round the edges of the lollipop. “It’s thrilling. One of them’s got lost and they think he’s perished miserably.”

“Be a sport,” said Roger. “I’ll tell you whether he did perish, if you don’t.”

“If you do, I’ll turn your underpants to ice,” Julia said amiably. “All right.” Without taking her eyes off her book or the lollipop out of her mouth, she fumbled out her handkerchief and tied a knot in it. She laid the knotted handkerchief on the arm of her chair and went on knitting.

Cat’s fallen soldiers picked themselves up from the floor and straightened their tin tunics. This was a great improvement, though it was still not entirely satisfactory. Cat could not tell his soldiers what to do. He had to shoo them into position with his hands. The soldiers did not seem happy. They looked up at the great flapping hands above them in the greatest consternation. Cat was sure one fainted from terror. But he got them positioned in the end – with great cunning, he thought.

The battle began. The soldiers seemed to know how to do that for themselves. Cat had a company in reserve behind a cushion and, when the battle was at its fiercest, he shooed them out to fall on Roger’s right wing. Roger’s right wing turned and fought. And every one of Cat’s reserve turned and ran. The rest of his army saw them running away and ran too. In three seconds, they were all trying to hide in the toy cupboard, and Roger’s soldiers were cutting them down in swathes. Roger was exasperated.

“Julia’s soldiers always run away!”

“Because that’s just what I would do,” Julia said, putting out a knitting-needle to mark her place in her book. “I can’t think why all soldiers don’t.”

“Well, make them a bit braver,” said Roger. “It’s not fair on Eric.”

“You only said make them move,” Julia was arguing, when the door opened and Gwendolen put her head in.

“I want Cat,” she said.

“He’s busy,” said Roger.

“That doesn’t matter,” said Gwendolen. “I need him.”

Julia stretched out a knitting-needle towards Gwendolen and wrote a little cross in the air with it. The cross floated, glowing, for a second. “Out,” said Julia. “Go away.” Gwendolen backed away from the cross and shut the door again. It was as if she could not help herself. The expression on her face was very annoyed indeed. Julia smiled placidly and pointed her knitting-needle towards Cat’s soldiers. “Carry on,” she said. “I’ve filled their hearts with courage.”

When the dressing-gong sounded, Cat went to find out what Gwendolen had wanted him for. Gwendolen was very busy reading a fat, new-looking book and could not spare him any attention at first. Cat tipped his head sideways and read the title of the book. Other-world Studies, Series III. While he was doing it, Gwendolen began to laugh. “Oh, I see how it works now!” she exclaimed. “It’s even better th

an I thought! I know what to do now!” Then she lowered the book and asked Cat what he thought he was doing.

“Why did you need me?” said Cat. “Where did you get that book?”

“From the Castle library,” said Gwendolen. “And I don’t need you now. I was going to explain to you about Mr Nostrum’s plans, and I might even have told you about mine, but I changed my mind when you just sat there and let that fat prig Julia send me away.”

“I didn’t know Mr Nostrum had any plans,” Cat said. “The dressing-gong’s gone.”

“Of course he has plans – and I heard it – why do you think I wrote to Chrestomanci?” said Gwendolen. “But it’s no good trying to wheedle me. I’m not going to tell you and you’re going to be sorry. And piggy-priggy Julia is going to be sorrier even sooner!”

Gwendolen revenged herself on Julia at the start of dinner. A footman was just passing a bowl of soup over Julia’s shoulder, when the skirt of Julia’s dress turned to snakes. Julia jumped up with a shriek. Soup poured over the snakes and flew far and wide, and the footman yelled, “Lord have mercy on us!” among the sounds of the smashing soup-bowl.

Then there was dead silence, except for the hissing of snakes. There were twenty of them, hanging by their tails from Julia’s waistband, writhing and striking. Everyone froze, with their heads stiffly turned Julia’s way. Julia stood like a statue, with her arms up out of reach of the snakes. She swallowed and said the words of a spell.

Nobody blamed her. Mr Saunders said, “Good girl!”

Under the spell, the snakes stiffened and fanned out, so that they were standing like a ballet skirt above Julia’s petticoats. Everyone could see where Julia had torn a flounce of a petticoat building the tree-house and mended it in a hurry with red darning wool.

“Have you been bitten?” said Chrestomanci.

“No,” said Julia. “The soup muddled them. If you don’t mind, I’ll go and change this dress now.”

Fire and Hemlock

Fire and Hemlock Reflections: On the Magic of Writing

Reflections: On the Magic of Writing The Game

The Game The Crown of Dalemark

The Crown of Dalemark Deep Secret

Deep Secret Witch Week

Witch Week Year of the Griffin

Year of the Griffin Wild Robert

Wild Robert Earwig and the Witch

Earwig and the Witch Witch's Business

Witch's Business Dogsbody

Dogsbody Caribbean Cruising

Caribbean Cruising Cart and Cwidder

Cart and Cwidder Conrad's Fate

Conrad's Fate Howl's Moving Castle

Howl's Moving Castle The Spellcoats

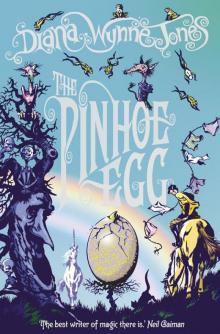

The Spellcoats The Pinhoe Egg

The Pinhoe Egg Drowned Ammet

Drowned Ammet The Ogre Downstairs

The Ogre Downstairs Dark Lord of Derkholm

Dark Lord of Derkholm Castle in the Air

Castle in the Air The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona A Tale of Time City

A Tale of Time City The Lives of Christopher Chant

The Lives of Christopher Chant The Magicians of Caprona (UK)

The Magicians of Caprona (UK) Eight Days of Luke

Eight Days of Luke Conrad's Fate (UK)

Conrad's Fate (UK) A Sudden Wild Magic

A Sudden Wild Magic Mixed Magics (UK)

Mixed Magics (UK) House of Many Ways

House of Many Ways Witch Week (UK)

Witch Week (UK) The Homeward Bounders

The Homeward Bounders The Merlin Conspiracy

The Merlin Conspiracy The Pinhoe Egg (UK)

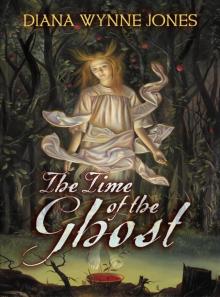

The Pinhoe Egg (UK) The Time of the Ghost

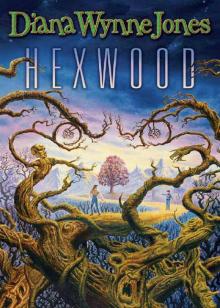

The Time of the Ghost Hexwood

Hexwood Enchanted Glass

Enchanted Glass The Crown of Dalemark (UK)

The Crown of Dalemark (UK) Power of Three

Power of Three Charmed Life (UK)

Charmed Life (UK) Black Maria

Black Maria The Islands of Chaldea

The Islands of Chaldea Cart and Cwidder (UK)

Cart and Cwidder (UK) Drowned Ammet (UK)

Drowned Ammet (UK) Charmed Life

Charmed Life The Spellcoats (UK)

The Spellcoats (UK) Believing Is Seeing

Believing Is Seeing Samantha's Diary

Samantha's Diary Aunt Maria

Aunt Maria Vile Visitors

Vile Visitors Stopping for a Spell

Stopping for a Spell Freaky Families

Freaky Families Unexpected Magic

Unexpected Magic Reflections

Reflections Enna Hittms

Enna Hittms Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci

Mixed Magics: Four Tales of Chrestomanci